By John Engel

The phrase “a game of inches” has its roots in sports, particularly football, and has evolved into a metaphor for high-stakes situations where small differences determine success or failure, whether in sports, real estate, leadership, or life.

The phrase was immortalized by Al Pacino’s electrifying locker room monologue in Any Given Sunday: “You find out that life is just a game of inches… Because in either game — life or football — the margin for error is so small. I mean, one half step too late or too early, and you don’t quite make it… The inches we need are everywhere around us. They’re in every break in the game, every minute, every second. On this team, we fight for that inch.”

Knicks fans know a game of inches. Tyrese Haliburton tied Game 1 at 125 with a jumper at the buzzer, though his foot was on the line, making it a two-pointer and sending the game to overtime.

While not a sport, real estate is most certainly a game of inches. Precision in pricing, presentation, and positioning can create or destroy millions in value.

Pricing inches: While a home priced $25,000 too high might sit on the market for months, that same home priced right might generate multiple offers and exceed asking. That margin, a few percentage points, is often the difference between success and failure.

Staging and presentation inches: I’ve said it before and say it again: A poorly lit room, an untrimmed hedge, dirty windows, or the wrong paint color can shift perception from dream home to project. Buyers are emotional. First impressions hinge on tiny details that create or kill desire.

Negotiation inches: Deals hinge on small concessions: a closing date, service contract, a minor repair, or what’s included. I am working on a multi-million-dollar deal now in which the wheelbarrow has been specifically named in the contract as one of the things that stays. These inches move the deal forward or blow it up.

Timing inches: Listing a week earlier might avoid competition, while accepting an offer a day too late is a day too late. Never cut and dry, these are subjective inches of judgment gained from experience doing many deals over a career.

Legal inches: Failure to close out permits, identify a legal pool site or easement, or meet a deadline have scuttled deals. The contract is full of them. These are the literal inches, objective, and demand attention to detail.

In the early ’90s, I completed a large assignment for a client, but I was late and he wouldn’t pay me, saying, “It’s binary.” I didn’t understand. He meant close doesn’t count; you succeeded or didn’t. It was an expensive lesson I haven’t forgotten.

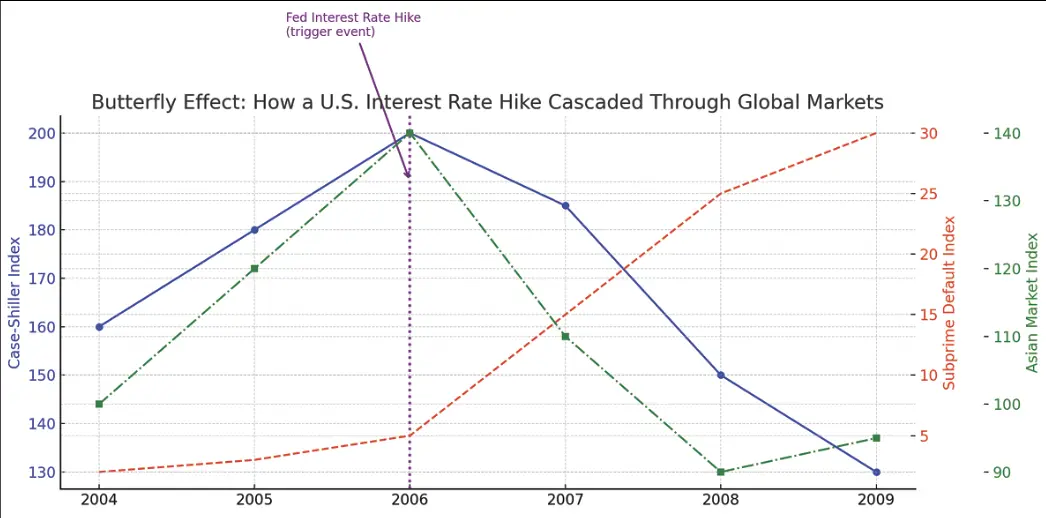

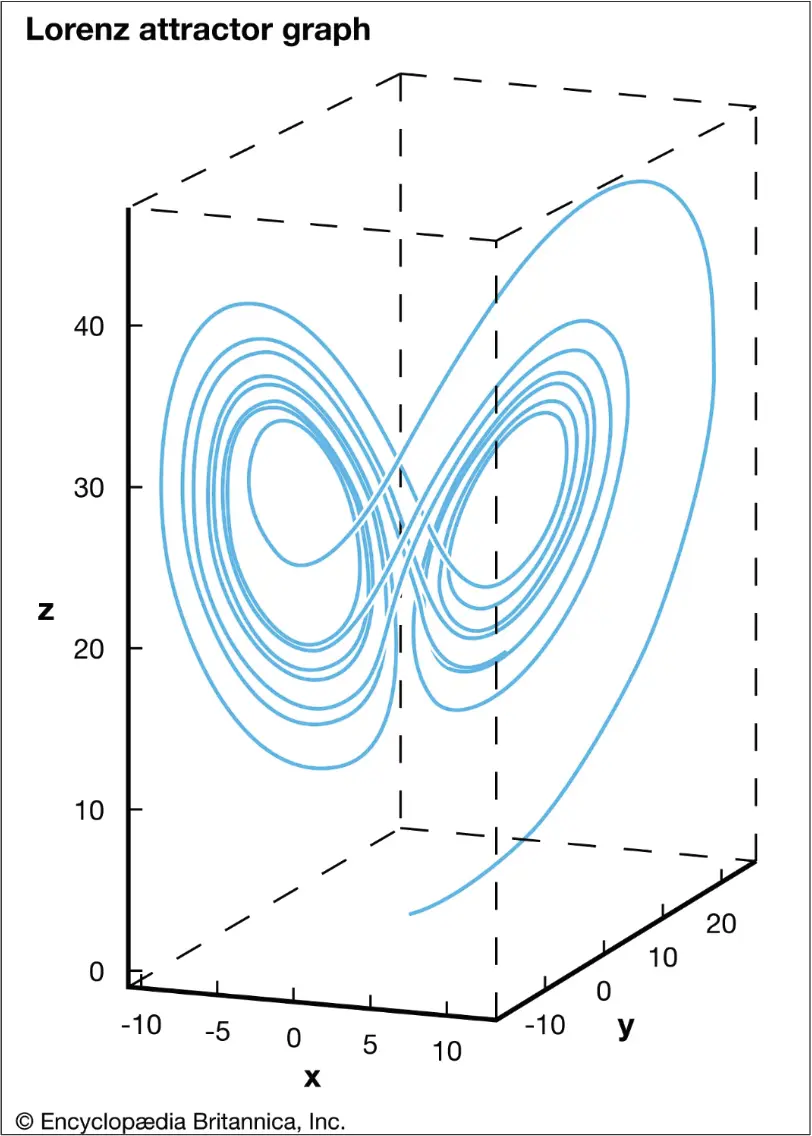

The second phenomenon, much less obvious, is the butterfly effect. This is the idea that tiny causes lead to large, unpredictable outcomes. (Like if you didn’t go to that party, you wouldn’t have met your wife.) While a game of inches is usually linear and cumulative, the butterfly effect is usually non-linear and exponential, where a small change leads to a massive shift. While real estate as a game of inches is about precision, control, and detail, real estate can also be a journey of unpredictability and sensitivity to initial conditions. Small things matter, but for very different reasons.

Where does this idea come from? Meteorologist and mathematician Edward Lorenz first asked, “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” in the early 1960s. He discovered that changing one tiny input value led to wildly different weather forecasts. Small causes can have massive, unpredictable effects in complex systems. But it was in Ray Bradbury’s 1952 short story “A Sound of Thunder” where a time traveler’s inadvertent killing of a butterfly in the past drastically alters the future, emphasizing the weight of seemingly minor actions. Ben Franklin anticipated the butterfly effect when he wrote in 1758 a variation of the 13th-century proverb, “For want of a nail.”

Are there modern-day examples of this principle, particularly in our real estate market?

The “IKEA Effect” is a variant of the theme describing what happens when a new building changes traffic patterns and spikes property values in the surrounding area. GE’s departure from Fairfield devastated Connecticut, while a potential Amazon move to Long Island City briefly buoyed the entire tri-state area.

In New Canaan, the decision by the Waze algorithm to re-route Merritt Parkway traffic through residential neighborhoods affects real estate values, not to mention has a profound effect on local families. To reverse the trend, we modify the inputs to the algorithm, adding a “no right turn” sign, slowing the neighborhood traffic and disincentivizing the detour.

The tree that blocked the view is another example. If a landscaper doesn’t trim the hedge before photos are taken, then the view is blocked, the buyer passes, the house sits, the next buyer offers $100,000 less, and that changes the comp set for the neighborhood. “There goes the neighborhood,” a phrase that dates to the ’40s, is now an idiom to mark any disruptive change, real or perceived, that can trace its roots to a particular event — maybe even that untrimmed hedge.

Covid Zoom towns are an example of unanticipated knock-on effects. In 2019, nobody thought remote work would shift demand, but the virus led to zoom policies, and that led to suburban and rural booms while crashing some urban cores. Despite corporate back-to-work mandates, we may never get that genie back in the bottle.

Focusing in, we see that every small decision — staging a room, choosing a buyer, fighting over the washer and dryer, delaying a listing — has the potential to trigger outsized consequences. Zooming out, we know that policy changes (we are about to rewrite New Canaan Zoning Regulations) and 8-30g legislation, pandemics, and buyer psychology (which can be altered by a single headline) can ripple across the region in massive ways that nobody could have predicted.

Notes from the Monday meeting

A multi-million-dollar sale is falling apart over the exclusion of four rugs. Another sale fell apart over the exclusion of the furniture last week, but a new buyer stepped up and scooped it up, unfurnished. We have a third example where the buyer wants the furniture and the seller has provided a spreadsheet with prices and sources. While Covid’s challenging supply chains provided an exception during which furniture had a moment, the sale of furniture is a complication most agents avoid for good reason.

John Engel is a broker with The Engel Team at Douglas Elliman, and he understands why furniture matters. Each piece tells a story. And some houses only make sense when they are furnished in a similar style. Frank Lloyd Wright believed “form and function are one” and created custom pieces for his houses, as did Marcel Breuer and Allan Gelbin. In contrast, New Canaan’s legendary furniture designer Jens Risom believed “Good design means anything good will go well with other equally good things.” Mix and match away, but keep in mind that Le Corbusier famously said, “Chairs are architecture, sofas are bourgeois.”