By John Kriz

Why Compost?

All animal and plant matter will decompose eventually. It might take weeks, years, or even decades, but it’ll happen.

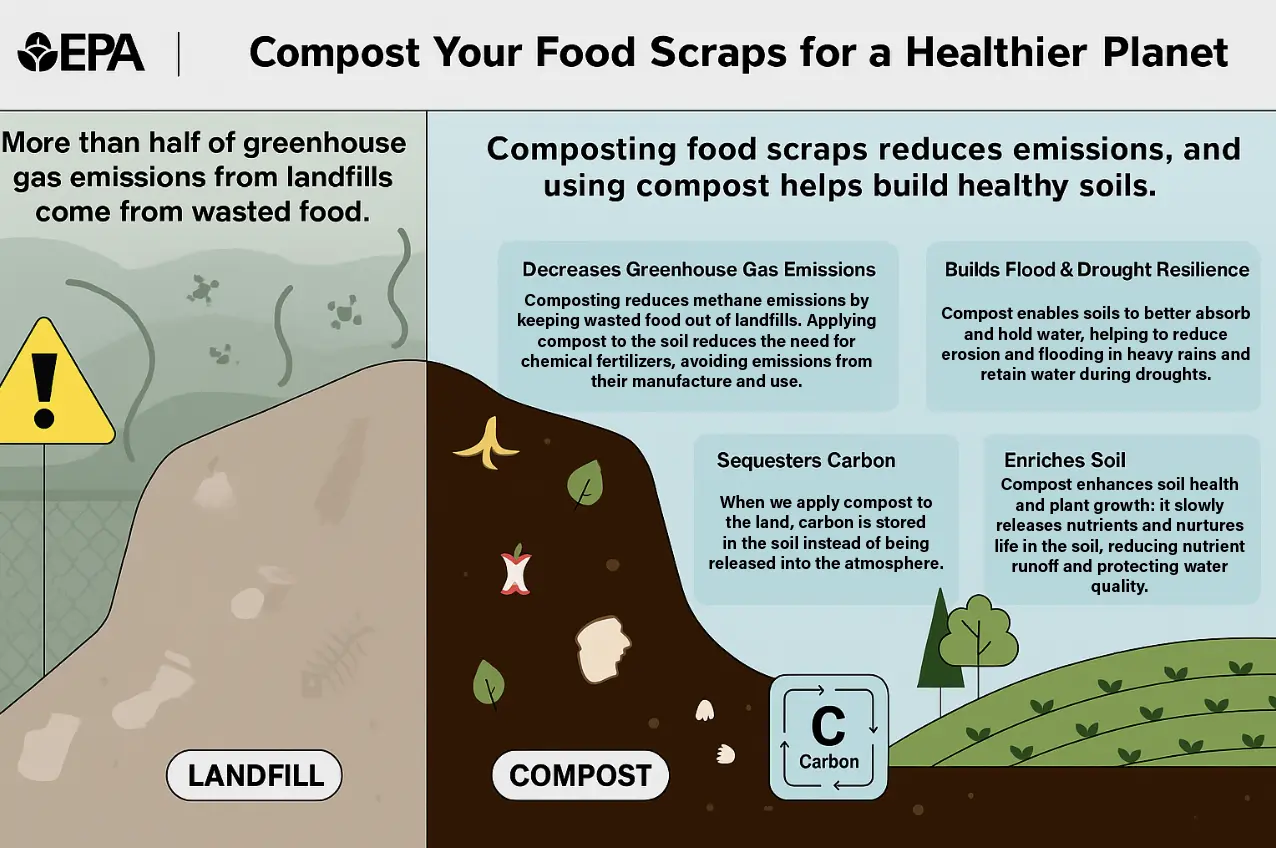

But how it happens matters. If you have garden or kitchen waste, it either is composted in some manner, or dumped in a landfill. However, when this food waste is buried in an airless, sunless landfill, it generates large amounts of methane gas, which is a particularly nasty greenhouse gas (GHG). Why is this? Though all decomposing plant and animal matter generates some methane, when such matter is composted, the decomposition process is under aerobic conditions – meaning oxygen is involved – and little methane is generated. When buried in a landfill, the decomposition is under anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions and that creates the high levels of methane.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency https://www.epa.gov/land-research/quantifying-methane-emissions-landfilled-food-waste “Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, is emitted from landfills, resulting from the decaying of organic waste over time under anaerobic conditions. Municipal solid waste landfills are the third-largest source of methane emissions from human activities in the United States. Food waste comprises about 24 percent of municipal solid waste disposed of in landfills. Due to its quick decay rate, food waste in landfills is contributing to more methane emissions than any other landfilled materials. An estimated 58 percent of the fugitive methane emissions (i.e., those released to the atmosphere) from municipal solid waste landfills are from landfilled food waste.”

Furthermore, per the EPA https://www.epa.gov/gmi/importance-methane “Methane is the second most abundant anthropogenic GHG after carbon dioxide (CO2), accounting for about 16 percent of global emissions. Methane is more than 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. Over the last two centuries, methane concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled, largely due to human-related activities. Because methane is both a powerful greenhouse gas and short-lived compared to carbon dioxide, achieving significant reductions would have a rapid and significant effect on atmospheric warming potential.”

Solution? Keep that food and garden waste out of landfills! In addition to substantially reducing methane emissions, you also generate compost, which is great for your garden, adding nutrients and organic matter.

Composting at the Transfer Station

If you don’t have composting space on your property, you can bring your kitchen scraps to the town’s Transfer Station and drop it in the compost bins there, which are on the far left of the big dumpsters where trash and recyclables go. In addition, the Transfer Station accepts bones and meat scraps to be composted because the raw waste is processed at a facility that can handle it.

These Transfer Station compost facilities are a cooperative project between the Town of New Canaan and local environmental charity Planet New Canaan www.planetnewcanaan.org which pays the cost differential between landfilling the kitchen waste and composting it. This subsidy paid by Planet New Canaan is about $300 a month.

Home Mechanical Composters

Another option are mechanical composters for the home. These units use electricity, and range in size from kitchen counter units to units about the size of a tall kitchen trash can that sit on the floor. Costs vary (some cost around $1000), as do how often they need to be emptied and whether they can process bones and meat scraps. These composters also shrink the volume of raw material by 80% or more. Note that if you live in an apartment or townhouse, there is the challenge of where to use the compost that’s generated.

New Canaan resident Gloria Hanson has had a mechanical composter in her home for a year, and likes it. Technically it is not a composter: It is more of a mill that fine grinds and dries her kitchen vegetable and fruit scraps. Composting uses micro-organisms such as fungi and bacteria to break down organic compounds. Some units you can buy are actual composters, but many are like Ms. Hanson’s: Mills that fine grind and dry the food waste. That said, the process takes only a few hours, and the machine is quiet – not any noisier as a dishwasher, she says. Her unit cost a bit over $200 and is “kind of big” so she keeps it in her garage. In addition, her unit cannot process bones or meat scraps. She hasn’t had issues with odors or leakage, but many units come with carbon filters that need to be replaced. The unit can jam, she says. You unjam it by unplugging it and pulling out any big chunks.

The end product consists of very small, dry particles which she dumps into a bucket in her garage, later mixing it with soil for her garden. She’s happy with the results.

Regarding these units that just fine grind and dry the food scraps, but do not actually compost the scraps, think of it this way: If a tree falls in the woods, it could take 20 to 30 years to decompose fully. If you were to take that tree, run it through a wood chipper, and spray the chips in the woods, it’d compost in a year or so. The ground, dry matter, such as what Ms. Hanson has, will decompose naturally and relatively fast once mixed with soil.

“It makes me feel like I’m doing something good,” says Ms. Hanson. “Plus I have a lot of garden, so I feel like I am using it to good effect and hopefully it’s helping my plants and at the same time I’m not throwing it [food scraps] in the garbage.”

Backyard Composting

Backyard composting is easy — really. If you spend over an hour/year managing it, you’re probably over-investing. And don’t worry. It won’t smell or attract nasty critters.

Here’s what you need to get started:

An outdoor compost bin. Metal mesh bins of about one cubic yard, with feet that go into the ground to keep it stable, are available over the internet or in many garden and hardware stores. Strictly speaking, you do not need a bin, but it helps. There are some expensive bins out there that you do not need.

Food scraps. ONLY use non-animal matter (though egg shells are OK). Plus lots of leaves. And we all have those. Bones and meat scraps attract nasty critters.

A container. Its job is holding kitchen scraps before putting them in the compost bin. There are plastic dog food containers that seal tightly and do not smell that work well. There are all sorts of expensive designer containers out there you do not need.

How to Do It…Eight Steps to Backyard Composting

1) Set up your bin. Exactly where on your property will vary. That said, it tends to blend in.

2) Fill the bin with dead leaves. And if there is ever any space in the bin, add more leaves.

3) Add your vegetable and fruit scraps. This can include items such as broccoli stalks, the tough ends of asparagus, and onion and fruit peels. (Note: Citrus peels compost slowly.) Be sure to cut everything up as small as possible. This will speed the composting process.

4) Add more leaves when the matter in the bin shrinks below the top.

5) Be sure the bin’s contents are damp. Things will compost faster this way. If rain is not doing the job, use a watering can or bucket.

6) Every month or so, stir the contents of the bin. Do the best you can. Don’t overthink it. A simple garden fork does the job. Why do this? You want to ensure that as much of the matter in the bin is exposed to air. Just like leaving leftovers uncovered in the fridge speeds up their spoilage, leaving compost undisturbed in a lump slows decomposition. What speeds decomposition are air, moisture and sun — and small pieces to decompose.

7) Keep adding new food scraps and those leaves. When in doubt, add more leaves.

8) When the bin has become full of solid matter (though it might need more time to be ‘fully cooked’), you’re done. How quickly does this happen? It depends on the amount of sun, air, moisture and stirring, and how small the scraps were when added.

Once the bin is full of solid matter (it’ll look like dirt) lift or dismantle the bin and move it to a new place, which is usually a few feet away. The not-quite-done compost will likely need more stirring to decompose those last items. At this point, a spade does a good job. When you cannot identify anything in the pile (because it has decomposed), it’s done.

Use that compost!

Further Pointers

• If it’s the dead of winter and your compost bin is a bit frozen (likely not going to happen often as decomposing matter kicks off heat), do not worry. You can keep adding material. Stir it up when there’s a thaw.

• Serious composters will have views on the right mix of so-called ‘brown’ and ‘green’ matter to add to the bin. While the composition of the mix can generate benefits, in the end, it’s not that big a deal. Most any compost you make will be beneficial.

• There are various so-called Compost Boosters sold in garden stores that can accelerate the decomposition process. You don’t really need them, though they can help.

• Do not use lawn grass clippings unless you do so Very Sparingly and are 100% sure there are no chemicals on them. This goes for everything you add. If you add food scraps that have been heavily sprayed with pesticides, insecticides and similar gunk, those chemicals end up in the compost. So, go organic, and you’ll be fine.

• Do not put any pet waste in the compost pile. Ever.

For the Hard Core

If you are really hard core, you will have a vermiculture bin in your basement (that’s worms in a specially made bin) and you’ll feed your kitchen scraps to them, producing more worms and worm castings (worm poop), which is fabulous for gardens. A topic for another day.

And Finally…

Home composting is cheap, easy and fun, and really helps the environment. If you have kids, make it a science project. But whatever you do, COMPOST!