By John Engel

Now that it’s September, we in Connecticut inevitably turn our eyes toward New York. It’s a season of rivalries, and while the Yankees and Red Sox may dominate the headlines, the deeper rivalry has always been with New York itself. Just as baseball loyalties run hot in September, our shared history, economy, and politics have stirred divisions and forged bonds that continue to shape real estate values here. This article traces that story: how war once divided us, how the railroad later united us, and why tomorrow’s drivers of value will be different. To understand today’s values, we need to look back at how conflict, infrastructure, and innovation defined this region.

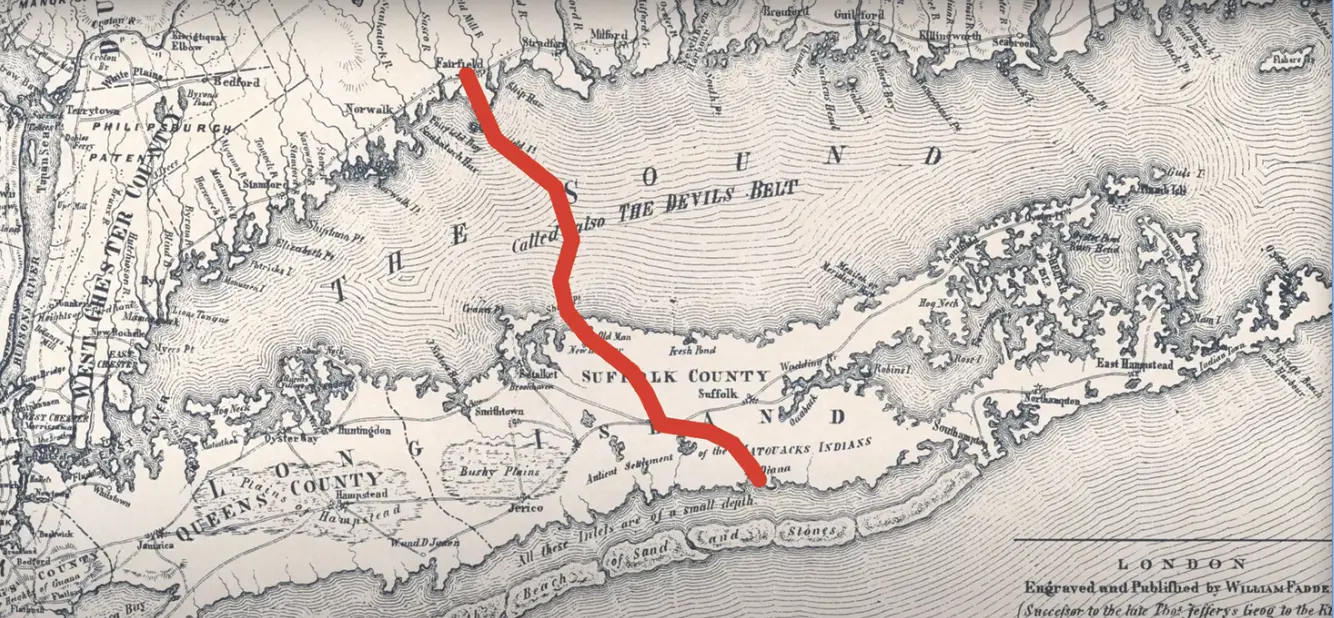

The Connecticut vs. New York rivalry first took root during the American Revolutionary War, when loyalties were tested not on a ball field but on the battlefield. In 1776, a 19-year-old Yale graduate, Benjamin Tallmadge (think Talmadge Hill), working as headmaster of Wethersfield High School, was called to replace Nathan Hale, Washington’s best spy, who had been executed by the British for espionage. Tallmadge’s assignment was to infiltrate British headquarters in New York City while also coordinating guerrilla raids across Long Island — raids that gave rise to what became known as the “whaleboat wars.”

From 1776 to 1781, bands of Connecticut teens rowed across Long Island Sound in 30-foot whaleboats, torching buildings, seizing supplies, capturing local officials, and hauling hostages back across the water. The British, of course, retaliated with larger armies, burning Norwalk to the ground and sending their own whaleboats to raid Connecticut shores.

Geography was politics. To live on Long Island was to side with the Crown; to live in Connecticut was to lean toward rebellion. Letters from the time even describe neighbors across the Sound as living on “the other side,” each coast defining the other as enemy territory. Washington himself exploited this divide, drawing heavily on Connecticut militias and Tallmadge’s Culper Ring of spies, whose success depended on the alignment of shoreline and allegiance. The cost of that alignment was steep: Loyalist families in New Canaan and Norwalk, such as Israel and James Hoyt (think Hoyt Farms), saw their ships destroyed and their property plundered.

Independence brought peace but not prosperity. Fairfield County emerged fragile, its farmland exhausted and its markets limited. Once again, the economy leaned on New York.

In the decades that followed, Connecticut slowly transitioned from a farming base to a manufacturing economy. Mills and factories rose along our rivers, harnessing water power to produce goods, while shipbuilding and coastal trade thrived out of harbors like Southport and Black Rock. This was a community reinventing itself, adapting from subsistence agriculture to a role within a regional economy increasingly defined by industry and commerce.

Yet even with new mills and coastal trade, Connecticut’s economic fortunes remained constrained until a single innovation rewrote the map: the railroad. No stagecoach or packet steamer matched the railroad’s impact when it linked Connecticut to New York in 1849.

At first, the railroad ran on freight — nearly 70% of its revenue — powering local industry and connecting Connecticut goods to New York markets. But it was the remaining 30%, the passenger business, that reshaped our communities. The ability to travel quickly to and from New York gave Connecticut towns a new identity and made proximity to a station a powerful driver of land values. Parcels near depots jumped to five or even ten times their former worth.

The effect was immediate and dramatic: Stamford’s population doubled between 1840 and 1860 to 8,000 residents, then swelled by another 50% by 1880. The railroad didn’t just move freight; it carried people, ambitions, and entire communities into a new era.

The numbers tell the story even more vividly. In Glenbrook, as they laid track in 1866, J.M.B. Whitton of Philadelphia paid $7,000 for 19 acres beside the upcoming line, roughly $370 an acre, just five miles from Stamford’s downtown. A year later, John Konvalika purchased an adjacent 15-acre parcel for $6,000. For perspective, average Connecticut farmland at the time was worth only about $30 an acre. The railroad created more than a tenfold premium overnight.

New Canaan saw a parallel transformation. Once, a modest farm of 22 acres could be had for $800 in 1783, and even as late as 1837, a small farm still sold for $6,000. Then prices skyrocketed once the trains arrived. By 1869, land was commanding $800 to $1,500 per acre. Shops and homes quickly sprang up to serve the growing population, and what had been a quiet farming town took the shape of a commuter suburb.

For more than a century, the one-hour train ride to Manhattan was Fairfield County’s greatest advantage, shaping not just our growth but our very identity. The railroad didn’t just carry freight and passengers — it carried the promise of a life balanced between city opportunity and suburban refuge.

But what happens when that balance shifts? If daily commuting once defined us, what is New Canaan’s relationship to New York now, when so few make the five-day journey into the city? Can we still be called a “bedroom community” if the bedrooms are full but the trains less so? The question forces us to consider whether proximity alone still drives value, or if other forces have taken the lead.

If commuting once defined New Canaan, schools have long sustained it. For generations, families have chosen Connecticut for the excellence of its public and private schools, and those schools in turn have been funded by the prosperity of Wall Street and midtown Manhattan jobs. The formula was clear: Parents came for the schools, developed roots, and stayed for the quality of life.

But in an era of decentralization — when finance, media, and technology are no longer tethered solely to Manhattan — can we count on those same jobs to support our greatest legacy? The question is more than academic: New Canaan is contemplating a new school at a multi-hundred-million-dollar cost, one that will more than double the town’s debt. It forces us to ask whether the historic advantages of education and quality of life will continue to sustain property values in the decades ahead. Can we afford it? Can we afford not to?

At the same time, the broader definition of advantage is shifting. While many residents eventually leave for warmer or less expensive parts of the country in retirement, those who can afford Connecticut often keep a foothold here, precisely because of the lifestyle and schools. And increasingly, location is not only about commuting to New York but also about connectivity to the wider world. Living between four major airports has become a modern advantage in its own right, reshaping how buyers think about value in a global economy.

Just as war once divided us and the railroad once united us, today another force is reshaping our future: artificial intelligence. AI is driving the stock market and promises to fuel the economy for decades to come, much as the microchip and the Internet did before it. The question is whether New Canaan is positioned to benefit.

The challenge is real. Connecticut pays the highest electricity rates in the nation, and an AI-powered economy is energy-hungry. Data centers will find cheaper homes elsewhere, and the cost of living here will remain high. But the opportunity lies not in housing the machines; it lies in housing the people who own and finance the machines. To capture the upside of AI, towns like New Canaan must remain magnets for the knowledge workers who design, build, and deploy this technology.

And that brings the story full circle. Our real strength has never been in freight or factories, nor in data centers, but in attracting families who value education, quality of life, and global connectivity. That is where New York, and New Canaan, continue to shine — not as rivals, but as partners in shaping the next chapter of prosperity.

John Engel is a broker on the Engel Team at Douglas Elliman in New Canaan. This week, a Florida custom suit maker asked John’s help opening shops in Greenwich, Westport, and New Canaan. Retail. Men’s suits. Tailoring. Downtown. Excellence is always in style.