By the Rev. John Kennedy

One of the very earliest figurative representations of Christ that we have—one of the earliest artistic depictions of Jesus—is Christ the Good Shepherd, carrying a lamb on his shoulders.

This image is drawn from the Parable of the Lost Sheep in the Gospel of Luke, which was the Gospel passage for Sunday, September 14 in the Episcopal Church (and other churches that follow the Revised Common or Roman Catholic lectionaries.)

In it, Jesus says: “Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? When he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices.”

The earliest known example of this image of Jesus is found in the Roman catacombs from the early third century. It is a moving depiction that can inspire deep love for Jesus, just as it powerfully conveys his deep love for us. At the same time, it was a way of portraying Christ in a symbolic, non-threatening, and slightly coded form. Christianity was not yet legal in the Roman Empire, and Christians routinely faced persecution. To portray Christ in a discreet manner made sense.

The image was rooted in biblical references familiar to us: Jesus’ Good Shepherd discourse in John chapter 10, Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd…”), and, as we have seen, the Parable of the Lost Sheep. But it also drew upon a familiar Greco-Roman image: the kriophoros—literally, “ram-bearer.” This was often an image of the god Hermes, or simply a shepherd, carrying a ram or lamb (or sometimes a bull) on his shoulders.

In this context, the animal carried on the shoulders was often a sacrificial victim. Sacrifice was central to ancient religious life, seen as a way of gaining divine favor, averting divine anger, purifying a community after a crisis or hardship, or marking festivals or solemnities such as Passover.

Sacrifice helped preserve group identity and cohesion, in part by projecting and transferring feeling of guilt, shame, or grievance onto a victim that would be sacrificed or cast out, taking away communal conflicts and tensions with it. A striking example of this is the Day of Atonement scapegoat ritual found in the Book of Leviticus. The high priest would confess the sins of the people over a goat’s head (the scapegoat), and then send it into the wilderness, thus bearing away the people’s sins. Similar practices of transference and projection existed throughout the ancient world.

The underlying message was something like this: someone, or some animal, must die so that the community can live.

We may no longer practice animal sacrifice (our excessive meat consumption aside), but scapegoating continues. As a people, and as a nation, we remain in a spiral of sacrificing one another on the altars of political and cultural allegiances and agendas. Too often, we preserve our group cohesion by excluding or condemning others. Too often we, imagine the problem lies with “them,” whoever “they” are. We deceive ourselves into believing that peace comes by getting rid of them, banishing them, cancelling them, sometimes even attacking or destroying them. The horrific political violence of recent weeks and months makes the reality of this problem all too clear.

Against this backdrop, I find it striking that early Christians adopted the image of a man carrying an animal on his shoulders not as a sign of sacrifice, but as a sign of salvation. The lamb is no longer a victim but a beloved sheep—sought, found, carried, and rejoiced over by the shepherd. The image is inverted, just as the Kingdom of God inverts the ways of the world.

Jesus taught us to love our enemies, to forgive, to do good to those who hate us. He taught that the greatest will be the servant of all, that those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted. Jesus sacrificed no one; he excluded no one; he did violence to no one. Instead, Jesus himself became the sacrificial lamb—the Paschal Lamb, the scapegoat—so that we might stop scapegoating and sacrificing one another.

Of course, scapegoating in our national and political life is unlikely to stop soon. But the Church exists to witness to another way. The Church is where we hear the Good Shepherd’s voice, where we are saved, rescued, and healed from violence, hostility, and division.

This is not only about our own personal salvation, as important as that is. The Good Shepherd is also an image of the Church itself. We are Christ’s body, his presence in the world. We are called not to judge and exclude, but to embrace and seek the good of all. Jesus discriminated against no one. Neither should we.

It may seem, especially in times like these, that there is little cause for rejoicing. Yet in the parable, when the shepherd finds the lost sheep and lays it on his shoulders, he rejoices, calling friends and neighbors to rejoice with him. Jesus says there is more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine who need no repentance.

So too, there is cause for rejoicing in the Church. For here we find a community in which our many and deep differences are held together by a deeper, wider love—a love that transcends what divides us. We can rejoice that we are lost sheep whom the Good Shepherd has found and carried, gathered together with all the other lost sheep into one flock, one body, one people of God. Together, we are called and equipped to witness to another way: the way of love in a broken world.

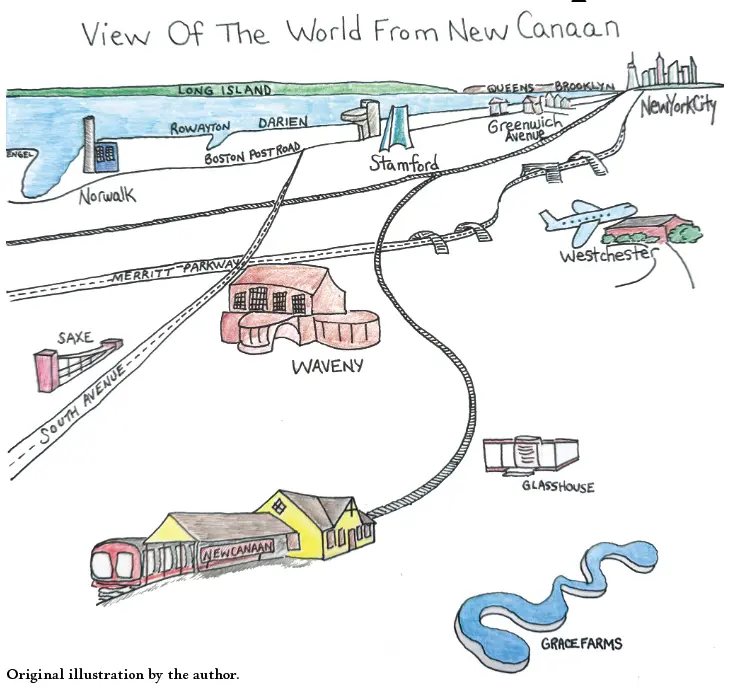

The Rev. John Kennedy serves as Associate Rector at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in New Canaan.