By John Engel

Walk through New Canaan’s wooded back roads and you can read the history of modern architecture written in glass, stone, and timber. The Glass House (1949, Philip Johnson), Noyes House (1955, Eliot Noyes), Boissonnas House (1956, Philip Johnson), Hodgson House (1951, Philip Johnson), and Tirranna House (1955, Frank Lloyd Wright) form the opening chapter. They are the canonical five that made this small Connecticut town one of the world capitals of mid-century design. Each is a declaration: Philip Johnson’s Glass House, a manifesto of transparency; Eliot Noyes’ own home, a humane refinement; the Boissonnas and Hodgson Houses, mature expansions of Johnson’s vision; and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Tirranna, the late master wrapping his Usonian poetry (his uniquely American language of low roofs, native stone, and open plans) around a waterfall.

By the 1960s, the modernist experiment had matured. The first wave of New Canaan’s modern houses had been conceived in the optimistic austerity of the postwar years; it was minimalist, abstract, and experimental. These houses were architectural manifestos built for architects and art collectors, not for growing families or New England winters.

But the world changed. The Baby Boom brought larger families; prosperity encouraged comfort and privacy; energy costs and New England’s climate demanded shade, insulation, and shelter. The revolution that had started as pure geometry learned to live comfortably with the messy demands of family, climate, and time.

Into that new world stepped Allan Gelbin, a former apprentice of Frank Lloyd Wright. He brought with him the master’s philosophy of organic architecture — buildings that grow from their sites — yet he adapted it to modern life. In 1955, he supervised the building of Tirranna for Wright. By 1957, he had established his own practice in Connecticut. In the Leuthold House (1966), Gelbin achieved what Wright had only hinted at: a house that was not merely poetic, but practical; not just expressive of nature, but truly livable within it. It was the moment when the student refined, and in some ways surpassed, the master.

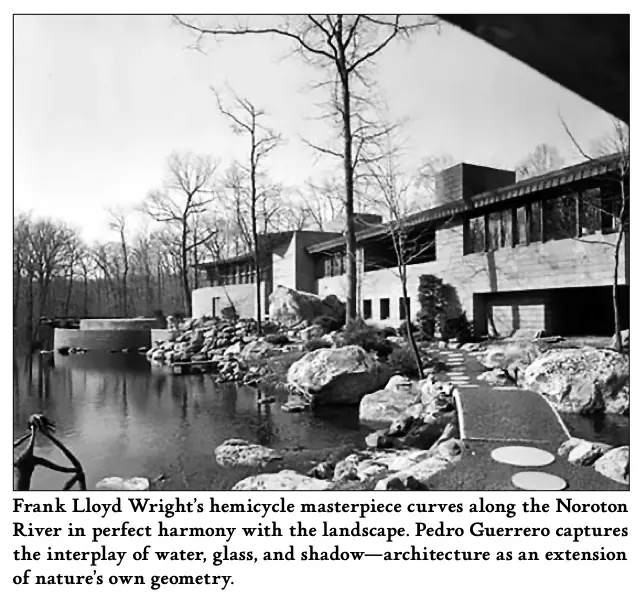

Set high above West Road on five acres, the Leuthold House commands its own landscape the way Tirranna nestles into its ravine. Wright’s Tirranna is a masterpiece of enclosure — a curved composition of concrete block and water, heavy with shadow and gravity. Gelbin’s Leuthold, by contrast, rises into light. Its broad overhangs shade glass walls; its terraces invite you outdoors. The roofs are green and alive, blending the architecture into its surroundings. The lake below is man-made but looks ancient, the reflection of the house rippling like a mirage. Where Wright’s architecture clings to the earth, Gelbin’s seems to hover just above it.

By mid-century, many of the purest modern houses — Johnson’s Glass House (1,800 sq. ft., one bedroom), Noyes’compact 2,000 sq. ft. family home, Breuer’s and Wiley’s small pavilions — had already outgrown their original purpose. Families expanded, lifestyles changed, and most of those icons have since been enlarged or altered.

The Leuthold House needed no such apology. At over 6,000 sq. ft., with separate guest quarters, open living spaces, and terraces that extend the interior outward, it was modernism built for how people actually live. The glass walls capture the view; the deep eaves shade the rooms and invite you outside. The enormous pool — so vast, it feels ready for a naval battle (and occasionally hosts one, in miniature) — turns recreation into landscape art.

If The Glass House was a laboratory for ideas, Leuthold was the prototype for living. It retains the intellectual clarity of its predecessors but adds generosity, comfort, and joy.

Culture loves a story where the student refines what the teacher began — Michelangelo completing Brunelleschi, Luke surpassing Obi-Wan, Jobs transcending his mentors. Architecture has its own moments of succession. The Glass House was a purer realization of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House — same idea, better executed, on friendlier ground. The Leuthold House performs a similar feat with Wright’s legacy: it’s a more livable evolution of the master’s organic ideals.

Wright’s Tirranna is a masterpiece, but it is a difficult house; with of stacked cinderblocks, it is heavy and intimate, its curves beautiful yet confining. Gelbin took those lessons and opened them to the sky. He traded the master’s gravity for lightness, enclosure for expansion. His curving glass wall is not merely decorative; it is a panoramic embrace of the landscape, as if the house itself were turning its head to admire the view.

By the time Gelbin was building in New Canaan, the Harvard Five had already secured the town’s place in architectural history. What followed — architects like John Black Lee, Hugh Smallen, Victor Christ-Janer, James Evans, and Allan Gelbin — was not imitation but maturation.

These architects proved that modernism could adapt, that glass and concrete could coexist with stone walls and woodlands, that elegance and warmth were not opposites. Among these, the Leuthold House stands tallest — literally, on its rise above West Road, and metaphorically, as the moment when modernism learned to breathe.

Of the roughly eighty moderns remaining in New Canaan, perhaps five define the first generation, and perhaps one defines what came after. Leuthold belongs to that second wave: confident, comfortable, utterly at home in its setting.

Today, as preservationists and collectors rediscover New Canaan’s moderns, the Leuthold House deserves its place alongside the legends. It represents not just an architectural style but a philosophical achievement: the reconciliation of art and life.

Standing on its terrace, watching the light change across that vast, reflecting pool, you understand why these houses endure. They are not relics of the 20th century; they are blueprints for how to live gracefully in any century.

In a town blessed with masterpieces, the Leuthold House may be the most complete, the point where the modern movement, and perhaps Allan Gelbin himself, finally arrived.

John Engel is a broker with the Engel Team at Douglas Elliman in New Canaan. His mother, Susan Engel, sold Tirranna in the 1980s, and her brothers, Franc and Brian Casey, restored its woodwork at that time. As a teenager, John had the rare chance to see the house up close — to walk those curves, touch the mahogany panels, and witness the architecture that defined a generation. Decades later, as a broker and student of design, he recognizes how Gelbin’s Leuthold House carried that legacy forward — proof that great architecture does not end with the masters, but continues with those they inspire.