By Emma Barhydt

In May 2023, Heritage Crafts released the fourth edition of its Red List of Endangered Crafts, a comprehensive assessment of traditional craft skills practiced in the United Kingdom and their long-term viability. Evaluating 259 crafts, the report classified each according to risk—viable, endangered, critically endangered, or extinct—offering a rare, systematic account of how well these skills are being passed from one generation to the next.

Though the Red List is a UK initiative, its framework has proven widely resonant. No equivalent national inventory exists in the United States or Canada, but the same questions surface repeatedly across North America in ecological studies, museum conservation efforts, Indigenous cultural programs, and apprenticeship initiatives: who still knows how to do this work, and who is learning from them?

Heritage Crafts defines a heritage craft as a practice rooted in manual skill, traditional materials, and techniques developed over at least two generations. Viability is measured not by visibility or commercial success, but by transmission. A craft survives only if there are enough practitioners actively teaching it.

That focus has sharpened attention on skills that tend to disappear quietly. In the UK, several crafts have already crossed into extinction within the past generation, including hand-stitched cricket ball making, gold beating, lacrosse stick making, mould and deckle making, and mouth-blown sheet glass making. Their disappearance was gradual, often unnoticed outside specialist circles.

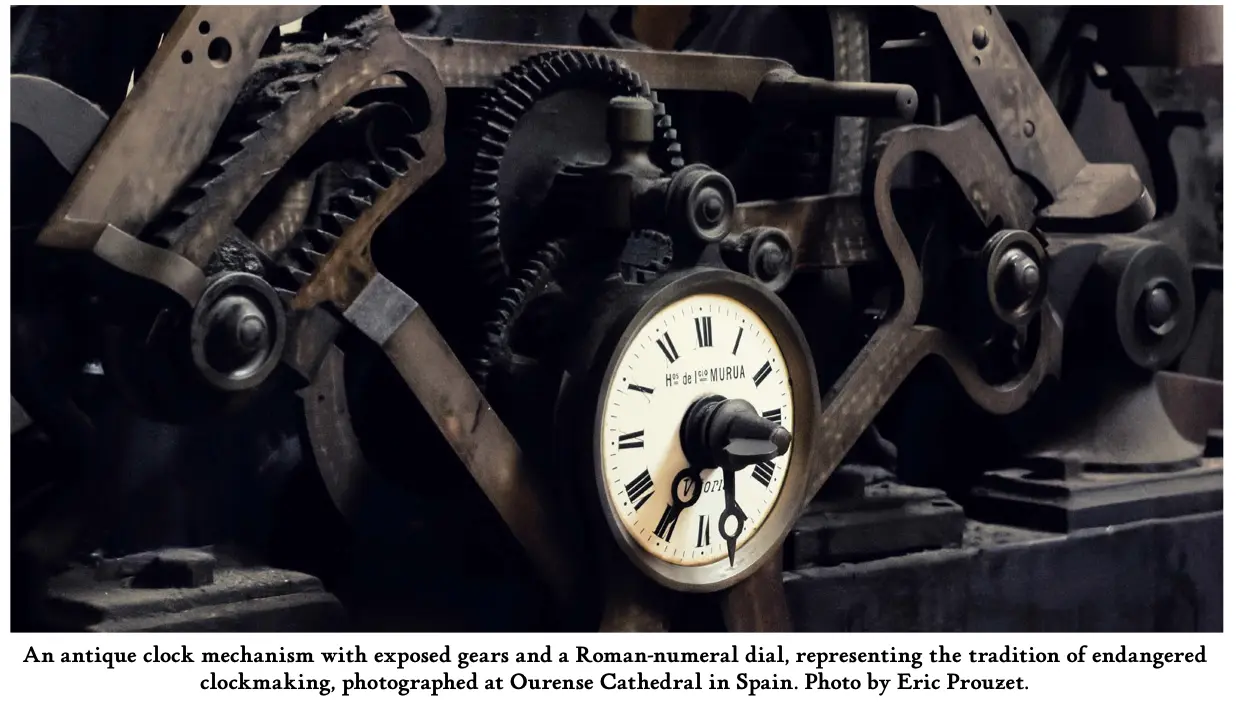

The critically endangered category is broader and includes trades once central to daily life and industry: bell founding, piano making, watchmaking, clog making, parchment and vellum making, and scientific instrument making. In some cases, fewer than ten people remain able to practice a craft professionally. The reasons are familiar—lengthy apprenticeships, high material costs, limited training routes, and an aging practitioner base.

The critically endangered category is broader and includes trades once central to daily life and industry: bell founding, piano making, watchmaking, clog making, parchment and vellum making, and scientific instrument making. In some cases, fewer than ten people remain able to practice a craft professionally. The reasons are familiar—lengthy apprenticeships, high material costs, limited training routes, and an aging practitioner base.

Across the Atlantic, similar patterns emerge, though they are documented differently. In North America, the absence of a centralized registry means risk is often identified indirectly. Indigenous crafts, in particular, appear at the intersection of cultural transmission, land stewardship, and material access.

Black ash basketry, practiced by Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Wabanaki communities in the Great Lakes and Northeast, is one of the most closely studied examples. The craft depends on black ash trees now threatened by the emerald ash borer. Ecological projections suggest severe losses in coming decades, prompting responses that include seed collection, forest management, and renewed apprentice training. Basketmakers are working not only to preserve technique, but to sustain the living systems that make the craft possible.

Other North American traditions face different constraints. Chilkat weaving, practiced by Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian artists in Alaska and British Columbia, requires years of specialized instruction under master weavers. Birchbark canoe building, once widespread across the Northeast, survives today through workshops and community-led teaching often supported by museums and cultural centers. Native Hawaiian kapa (barkcloth) making, nearly eliminated by the early twentieth century, has been reestablished through sustained instruction, cultivation of traditional plants, and institutional partnership.

What distinguishes many of these efforts is that they are not attempts at reconstruction, but continuation. Teaching remains central. In both the UK and North America, the most effective preservation strategies involve direct transmission: mentor–apprentice programs, community workshops, and structured training that treats craft knowledge as something learned through time and repetition.

Heritage Crafts’ Red List draws on conservation models used by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, translating them to human skill. That language of risk has proven useful. It allows policymakers, funders, and educators to see craft not as an abstract cultural good, but as a system that can be stabilized—or allowed to fail.

The report’s visibility has grown accordingly. It has been launched at the House of Lords, cited in policy discussions, and featured in national media. King Charles III, Patron of Heritage Crafts, emphasized in the foreword to the original report the urgency of documenting skills before they are lost, particularly those reliant on tacit knowledge learned through observation rather than written instruction.

What the Red List also makes clear is that many heritage skills remain deeply relevant. Millwrighting, wheelwrighting, sail making, canoe building, natural fiber processing, musical instrument making, and ceremonial arts continue to shape public spaces, performance traditions, and working landscapes. Their future depends less on preservation in the abstract than on continued use.

There is evidence, quietly accumulating, that this work is happening. Apprentices are being trained. Materials are being stewarded. Young practitioners are entering fields once assumed to be closing. The Red List itself is revised regularly not only to document decline, but to track recovery where it occurs.

Ultimately, lists like these are not endpoints. They are tools for attention. They clarify where continuity is fragile, where it is holding, and where support can still make a difference. As long as teaching continues—hand to hand, generation to generation—these crafts remain alive.

EXTINCT: Cricket ball making (hand stitched); Gold beating; Lacrosse stick making; Mould and deckle making; Mouth blown sheet glass making

CRITICALLY ENDANGERED: Arrowsmithing; Basketwork furniture making; Bell founding; Besom broom making; Bow making (musical); Bowed felt hat making; Chain making; Clay pipe making; Clog making; Coiled straw basket making; Copper wheel glass engraving; Coppersmithing (objects); Currach making; Cut crystal glass making; Damask weaving (linen); Devon stave basket making; Diamond cutting; Encaustic tile making; Engine-turned engraving; Fabric flower making; Fabric pleating; Fair Isle straw back chair making; Fan making; Figurehead and ship carving; Flute making (concert); Fore-edge painting; Frame knitting; Glass eye making; Glove making; Hat block making; Hat plaiting; Highlands and Islands thatching; Horse collar making; Horsehair weaving; Industrial pottery; Linen beetling; Maille making; Matte painting; Metal thread making; Millwrighting; Northern Isles basket making; Orrery making; Paper making (commercial handmade); Parchment and vellum making; Piano making; Pietra dura; Plane making; Plume making; Pointe shoe making; Quilting in a frame; Rake making; Rattan furniture making; Saw making; Scientific and optical instrument making; Scissor making; Sieve and riddle making; Silk ribbon making; Silver spinning; Spade making (forged heads); Spinning wheel making; Straw hat making; Sussex trug making; Swill basket making; Tanning (oak bark); Tinsmithing; Wainwrighting; Watch dial enamelling; Watchmaking; Welsh vernacular thatching; Wooden fishing net making; Black ash basketry; Chilkat weaving; Birchbark canoe building; Kapa (barkcloth) making; Wampum shell bead making; Dugout canoe carving; Plains porcupine quillwork; Inuit drum making and ceremonial dance traditions

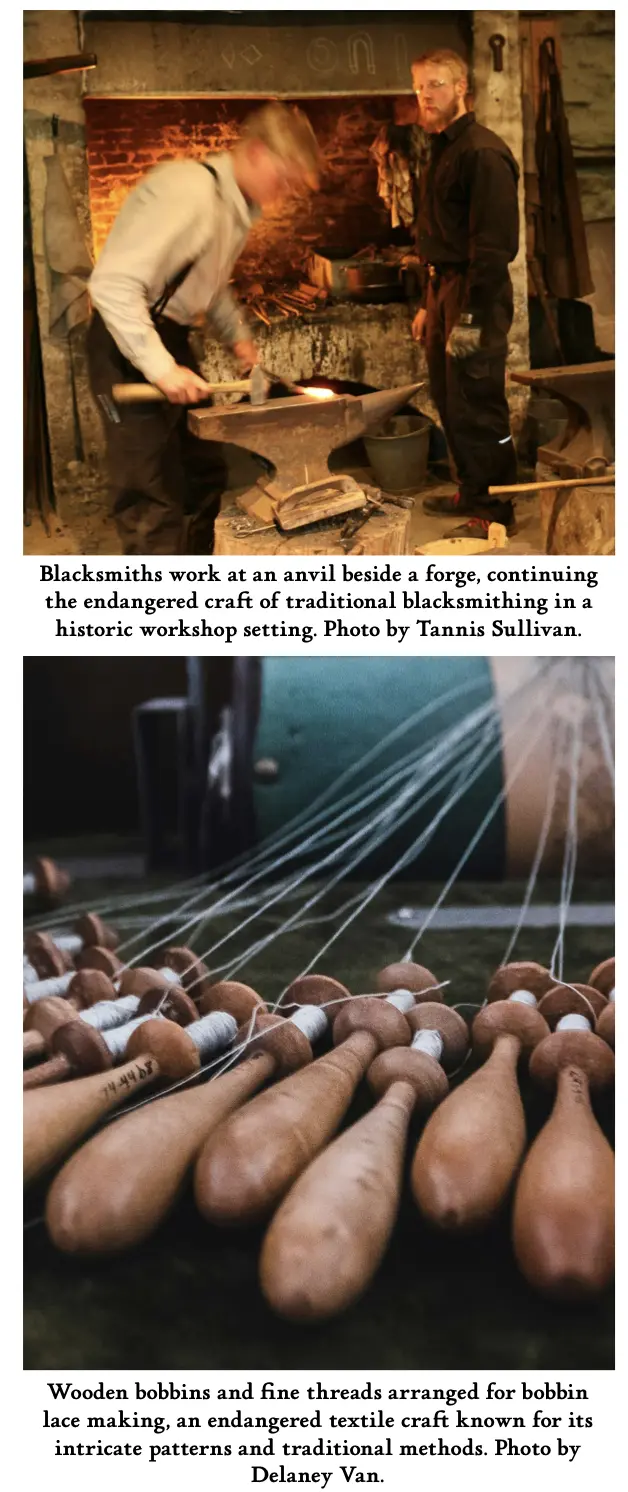

ENDANGERED: Armour and helmet making; Bagpipe making (Northumbrian pipes, smallpipes, bellows-blown pipes); Bee skep making; Bicycle frame making; Block printing (wallpaper and textiles); Traditional wooden boatbuilding; Brass musical instrument making; Brick making; Brush making; Canal art and boat painting; Clock making; Coach building and trimming; Composition picture frame making; Coopering (non-spirits); Coracle making; Corn dolly making; Cornish hedging; Cricket bat making; Fairground art; Flintwork (buildings); Free reed instrument making; Gauged brickwork; Globe making; Graining and marbling; Hand engraving; Hand grinding; Harp making; Hat making; Hazel basket making; Hewing; Historic stained glass window making; Horn, antler and bone working; Hurdle making; Illumination; Irish vernacular thatching; Keyboard instrument making; Kilt making; Lace making (bobbin lace); Lacquerwork; Ladder making; Letterpress; Lithography; Lorinery; Marionette making; Nalbinding; Neon making; Oar, mast, spar and flagpole making; Organ building; Orkney chair making; Pargeting, stucco and scagliola; Passementerie; Percussion instrument making; Pewter working; Pigment making; Pysanka egg decorating; Reverse glass sign painting; Rigging; Rope making; Rush matting; Sail making; Shoe and boot making (handsewn); Silk weaving; Silversmithing allied trades; Slate working; Spectacle making; Split cane rod making; Sporran making; Straw working; Vegetable tanning; Type founding; Umbrella making; Vardo art and living wagon crafts; Welsh tapestry weaving; Wheelwrighting; Withy pot making; Wooden pipe making; Woodwind instrument making; Sweetgrass basketry; Pueblo pottery; Métis jigging; Regional fiddle traditions; Native Hawaiian featherwork; Traditional blacksmithing; Saddle making; Hand drum making; Ceremonial dance traditions and regalia making; Regional folk dance traditions