By John Engel

Super Bowl Sunday ads were dominated by AI companies, the single largest category of advertiser. That felt like a signal. We are fascinated and afraid at the same time, curious about a future we don’t fully understand, eager to lean in, and quietly anxious about where usefulness ends and obsolescence begins. In 2026, people across industries are asking the same question: What part of my job can’t be done by a machine?

Every generation has to relearn what makes people useful, usually in response to new tools and new systems. What feels different now is how quickly that reckoning is arriving.

For most of us, that process begins early, when we first start to sort out what we like to do and what we’re good at.

If we’re lucky, those things align. But liking something, and even being good at it, doesn’t always translate into something useful in the real world.

In my case, book reports in high school led to majoring in English in college. College writing is persuasive by design: thesis, facts, conclusion. It felt like a useful skill to build a future around. You can be anything with an English major.

I leaned in, thinking writing might carry me into whatever came next. It was supposed to be a safe bet, the belief that writing was a durable skill that would remain useful across changing systems. That idea of usefulness turned out not to be true at all.

My first job out of college was as an Army officer, working inside a system that does things very differently. The first thing you learn in the Army is: Forget what you learned about writing in college. In the Army, we don’t write term papers. We write Operations Orders, all in the same five- paragraph format. “Etch these paragraphs in your brain.” And we did. This writing is nothing like school.

The five paragraphs describe the Situation, the Mission, and the Execution, followed by Service/ Support and Command/Signal. It’s a kind of writing not designed to be persuasive, like a thesis. Its purpose is to describe what comes next and how everyone works together to make it happen. It’s a formulaic style of writing that punishes creativity, rewards brevity, and is always on the clock. An Op Order goes to the commander immediately, usually within the hour.

But not all Army writing is about issuing orders. Staff officer writing is persuasive; its about making sense of incomplete information under pressure and advising the commander what comes next. That kind of synthesis is exactly where AI is starting to show up.

When I left the Army, I went to work at a marketing agency in Connecticut, and once again, the instruction was familiar: Forget what you think you know about writing.

Writing now meant sales letters, proposals, and PowerPoint slides — writing designed to persuade rather than command.

Different setting, different rules, and once again, a different definition of what made writing useful.

When the Internet arrived in the late 1990s, writing changed all over again. Websites weren’t read the way essays were read; they were scanned, navigated, abandoned. Structure, hierarchy, and clarity mattered more than voice, because the reader could leave at any moment.

For the first time, writing wasn’t just persuasive; it was precisely measurable.

Effectiveness could be tracked, tested, optimized, and improved, until “what worked” began to matter more than how it was written.

That brings us to 2026, where writing is being redefined yet again.

I’ve never thought of myself as having one job. I’ve thought of myself as having one skill that kept getting retrained. Writing was how I made sense of things as a student, as an officer, in marketing, and later in real estate. The setting kept changing, but the work was always the same: Take incomplete information, impose some order on it, and help someone decide what to do next.

That question feels especially sharp in 2026. Not because change is new, but because it arrives faster than reflection. It’s the same question we hear in conversations about careers, in offices, and at kitchen tables with kids who are just starting out. What am I actually good at, and what part of that still matters? Can I be replaced?

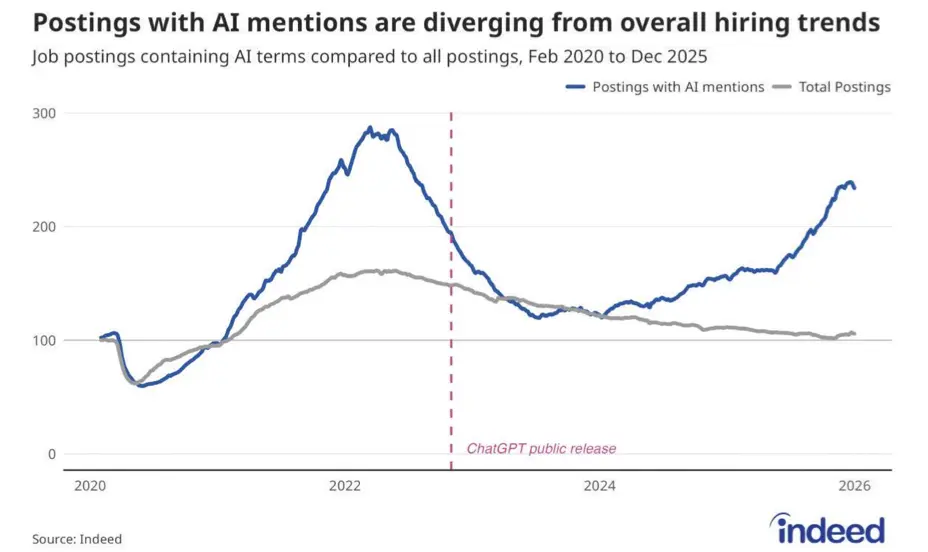

Which brings us, inevitably, to artificial intelligence.

The question isn’t whether AI can write. It can. What’s less clear is whether it can replace the parts of writing that actually make people useful.

I was struck by that distinction this weekend, listening to Deacon Bill’s homily that was thoughtful, grounded, and unmistakably human. It wasn’t impressive because of how it was written, but because of what it understood about the people listening. It could not have been written by a system trained on language alone.

AI has made it clear that producing language is no longer a scarce skill. What’s less clear is whether producing language is the work that actually matters.

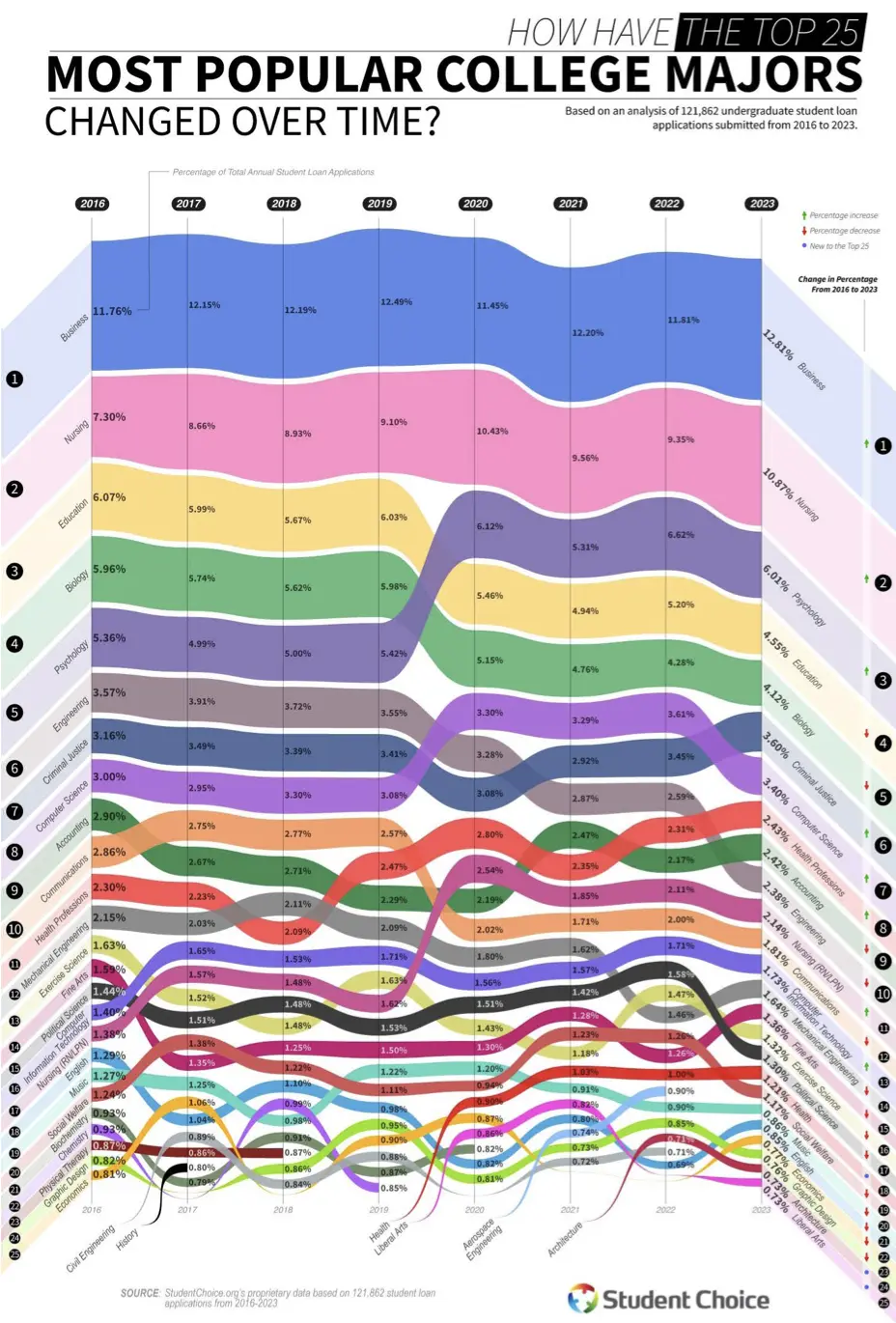

That uncertainty is hardest to ignore when you think about people still in school or just starting their careers. They’re being told, as every generation is, that the rules are changing. Learn something new? Let go of what no longer fits? Figure out how to be useful again. Learn to write. It never goes out of style.

This is also a real estate column, and a local one. In New Canaan, the value of our homes is still closely tied to the strength of our schools, and those schools are still judged on fundamentals that haven’t changed much over time. Reading. Writing. The ability to think clearly and communicate well.

If we’re looking for the things most likely to shift in an AI-powered economy, those basics probably aren’t among them.

So this isn’t a question about whether machines can write. Writing is just the place where the change is easiest to see. What’s really being renegotiated is usefulness. The underlying work of judgment, interpretation, and understanding hasn’t changed, even as the systems around it keep resetting the terms. Each time that happens, we mistake a new interface for a new problem. In 2026, the task is the same as it’s always been: Figure out what part of the work still belongs to us.

John Engel is a broker with the Engel Team at Douglas Elliman in New Canaan, and he writes. We all write. The average person writes 6.4 million words by text and 1.6 million words by email and reads many multiples of that, skimming as many as 490,000 words per day and reading between 150 and 600 million words in a lifetime. Where do they all go? The most important words are stored in our frontal lobes, called “semantic memory,” and that’s where you’ll find this column.