By Amelia Woodhouse

As Valentine’s Day approaches, expressions of love appear in their most compressed form. The flowers, the chocolates, the cards, the bottled spirits, the reservations all point toward a single, scheduled day.

Art history tells a different story. Across centuries, artists have returned to love as a subject that reflects how people imagine meaning. Traced over time, love in the arts reads as cultural evidence: shaped by belief, ritual, power, and place.

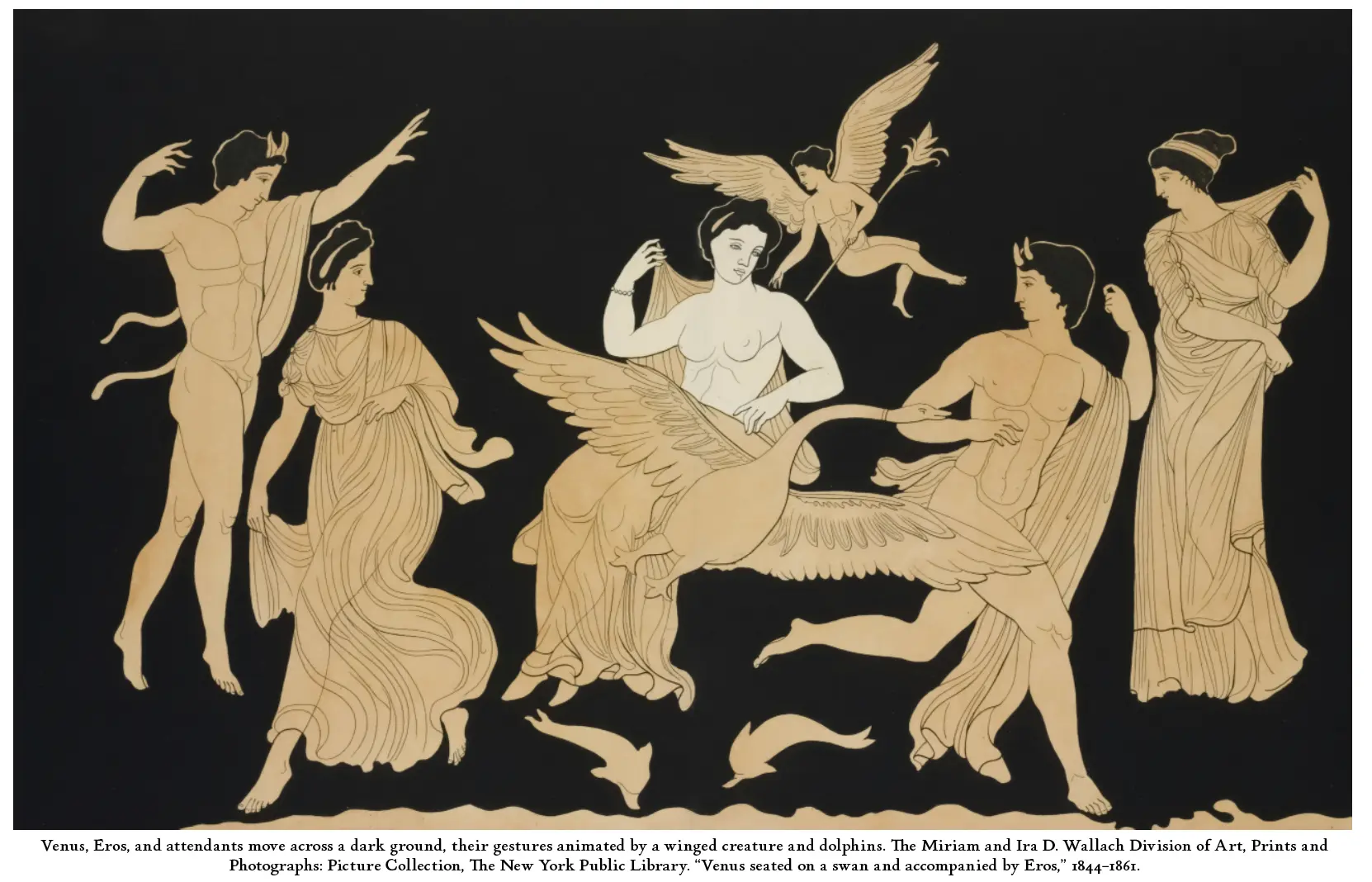

In the ancient world, love entered art with authority. Greek and Roman artists gave it divine form through Aphrodite and Venus, figures carved and painted as ideals of attraction, fertility, and influence. Desire functioned as a public force, tied to marriage, lineage, and civic order. Sculpture and poetry presented love as something that moved individuals and cities alike. Emotion carried weight and consequence.

During the medieval period, love took on structure. Courtly love emerged as a formal system that governed romance among the nobility. Poetry, song, and illuminated manuscripts presented devotion through rules of conduct: distance, loyalty, patience, longing. Love gained value through performance. Artists codified emotion into recognizable symbols, creating a shared language understood by audiences across regions. Romance became legible.

The Renaissance expanded that language. Classical mythology returned, yet artists also turned inward, examining private feeling with new intensity. Love appeared in portraits, domestic objects, and literature as a personal experience shaped by desire and reflection. Petrarch’s poetry helped circulate a model of love marked by fixation and introspection, influencing visual artists who echoed this emotional depth through gesture and expression. Art linked mythic imagery with human vulnerability.

By the sixteenth century, artists treated love as layered and ambiguous. Allegorical paintings packed multiple meanings into a single scene. Pleasure, time, jealousy, and deception coexisted in dense compositions that required careful reading. Works such as Bronzino’s symbolic studies invited viewers to linger, interpret, and debate. Love became an intellectual subject as much as an emotional one.

As Europe moved into the Enlightenment and early modern period, artists placed love within social frameworks. Paintings and plays examined courtship, marriage, and reputation. Domestic scenes and satirical works reflected how affection operated alongside class expectations and legal arrangements. Love functioned as negotiation, shaped by manners and public scrutiny. Art documented these dynamics with observational precision.

The Romantic movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries shifted focus toward intensity and individual experience. Artists elevated emotion as a primary source of meaning. Painters used landscape to mirror feeling. Writers and composers framed love as consuming and transformative. Opera embraced this scale, filling theaters with stories driven by devotion and sacrifice. Audiences gathered to experience heightened emotion together, drawn by the power of shared response.

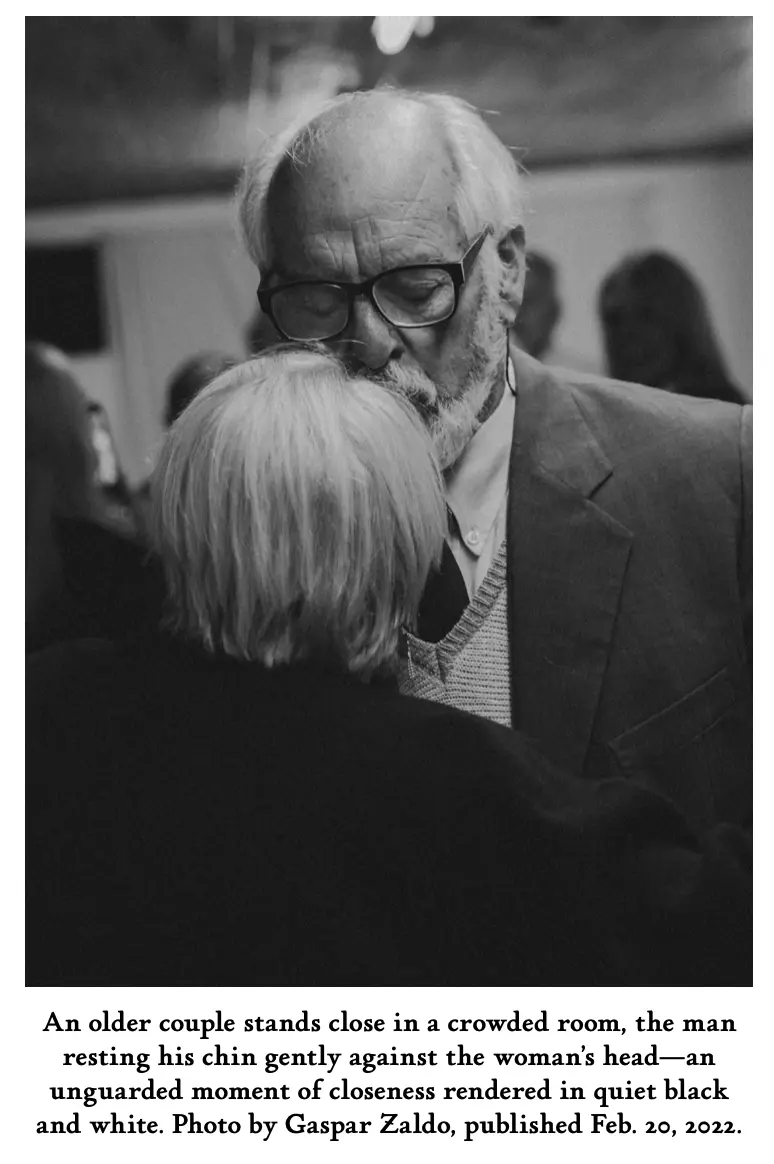

The arrival of modern life reframed intimacy again. Artists responded with scenes drawn from everyday life: couples in cafés, solitary figures, private interiors. Photography and film introduced new immediacy.

Across these periods, one pattern holds. Love in art thrives through visibility. Audiences play an active role, bringing attention and continuity to the work.

Artists have documented beautifully how people connect, commit, and belong. Their work endures because audiences continue to meet it with curiosity and presence.

This year Valentine’s Day is on Saturday so add a visit to a museum or catching a show to the list of flowers, chocolates, cards, bottled spirits, and restaurant reservations. Happy Valentine’s Day.