By John Kriz

February is Black History Month, declared in the Bicentennial year 1976 by former President Gerald Ford. Its precursor was Negro History Week, the idea of historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, in 1926; it was celebrated during the second week of February, to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

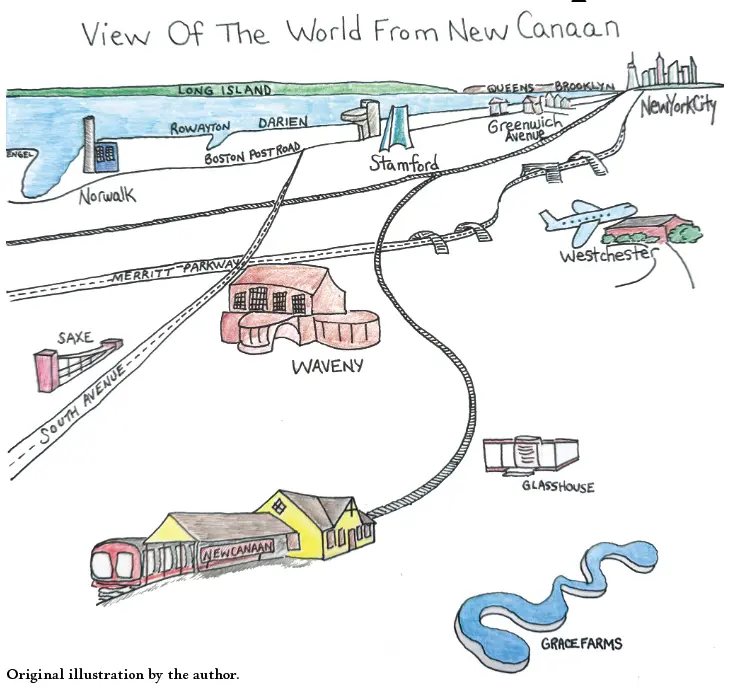

Black people have consistently lived in New Canaan since colonial times, though never in large numbers. According to mid-2025 U.S. Census estimates, Blacks comprised 1.7% of the town’s population.

From Colonial Times

According to documents and research from an exhibition at the New Canaan Museum & Historical Society entitled “Forces of Change: Enslaved and Free Blacks in New Canaan,” in 1776 Connecticut had more than 5,000 people in bondage, the most in any New England colony.

(Editor’s Note: The bulk of the information in this section has been taken from this exhibition, which was researched and produced by the New Canaan Museum & Historical Society https://nchistory.org in 2019 with a grant from the New Canaan Community Foundation.)

In 1784, ‘An Act to Prevent the Slave Trade,’ prevented residents from importing or transporting any inhabitants of Africa as slaves or servants for a term of years. It also stated that “No negro or mulatto born in Connecticut after March 1 is to be held as a slave after reaching the age of 25.”

The 1790 census noted that Samuel Cooke Silliman, son of Rev. Robert Silliman, owned a woman named Phyllis. Mr. Silliman died in 1795, and left his estate to his wife except for Phyllis, whom he emancipated. A month prior to his death, Phyllis gave birth to a son, Harry, who was listed as a ‘mulatto male child’. Phyllis died in the town’s almshouse at age 101. Later records indicate that Mr. Silliman’s widow purchased a ‘malato boy Harry’, turning him over to her brother.

A 1792 Connecticut law allowed slave owners to emancipate their slaves provided those persons were deemed to be in good health, and between the ages of 25 and 45 – dropping to 21 a few years later.

In 1800 Connecticut still had slaves among its population, though it had fallen to 931. The number of free Blacks had risen to 5,300. Many slaves had been emancipated by enlisting in the military during the Revolutionary War.

When New Canaan was incorporated as a town in 1801 the population of 1,500 included 8 slaves.

In 1818, the Connecticut Constitution was amended to exclude Blacks from voting.

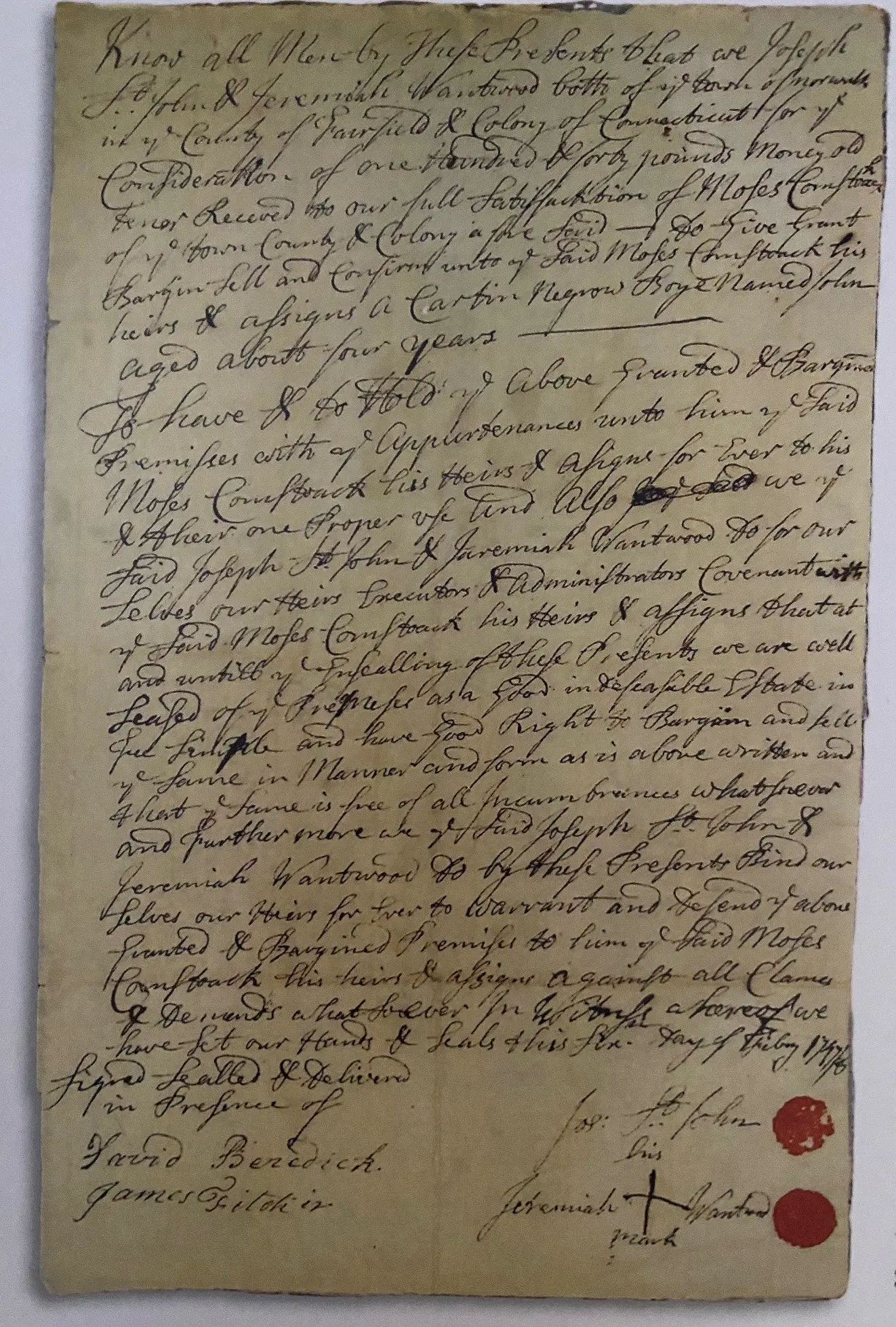

Records from 1790 to 1830 listed numerous New Canaan families as slaveowners, including such prominent surnames as Benedict, Carter, Comstock, Fitch, Hanford, Husted, Richards, St. John, Seely, Silliman and Weed – many now found in street names.

Connecticut enacted the ‘Black Law’ in 1833, which prohibited anyone from educating Blacks without authorization by a town’s government. This was in response to Prudence Crandall’s school for Black women in the town of Canterbury.

The Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1838.

Connecticut abolished slavery in 1848.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision ruled that Blacks could not be citizens, and that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories.

Onesimus Comstock, born to his enslaved mother Candace in 1763, in the household of Capt. Jonathan Husted, was sold at age ten to Sarah and Phoebe Comstock. In the 1850 census, Onesimus listed himself as a ‘voluntary slave.’ He died in 1857, and is buried in the Upper Canoe Hill Cemetery.

Miss Dinah Richards owned an estate on Smith Ridge Road, as well as slaves, one of whom was Grace. When Grace married, Miss Richards built a house for the couple on Laurel Road. Grace served as Miss Richards’ personal attendant and was a parishioner at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, where she helped serve the noon meal. She is buried in the Canoe Hill Burying Ground along with Miss Richards and many of Miss Richards’ family members. Grace’s headstone says: Grace, wife of Benjamin Smith, born in Congo, Lower Guinea, Africa. Died in New Canaan, Conn., June 18th, 1875. Aged about 80 years.

Census data from 1850 state that there were 22 Black people in New Canaan, rising to 37 by 1880.

Nancy Thatcher, a Black girl, was raised by Nathan and Mary Hanford, who were childless. She eventually married and had two children, with Mr. Hanford giving her seven acres of land on the Five Mile River. Mr. Hanford subsequently gave her the Hanford Homestead, including 68 additional acres. Her husband died and she remarried, giving birth to two more children. She died in 1881, age 56, leaving a substantial estate. She is buried in Upper Canoe Hill Cemetery.

Alice King, born in 1890 and of European descent, was active in the arts and in the NAACP. She saw the housing challenges that Blacks in New Canaan faced in having someone sell a house to them, and in securing mortgage financing from banks. She decided to become a de facto bank and realtor, buying a dozen homes on East Avenue and Cherry Street in 1941, first renting the homes to Black families, and then selling the homes to them. Most of these Black families owned small businesses. Working with the now-104-year-old Community Baptist Church on Cherry Street, a historically Black church, and other groups, she helped these small businesses to become more integral parts of the local business community, and for the families’ children to be enrolled in the town’s public schools.

(Editor’s Note: See https://www.newcanaansentinel.com/2024/03/29/community-baptist-church-small-church-big-heart/ for a detailed profile of Community Baptist Church.)

Beatrice Jeffress and her husband came to New Canaan in the late 1940s. She was the first Black person to serve in the New Canaan Police Department, first as a crossing guard and subsequently as supervisor for female prisoners. Their son Robert became a teacher and guidance counselor in New Canaan High School. He has been an active member of the Community Baptist Church for many years, including service as a church trustee.

Lucius Griggs founded New Canaan’s branch of the NAACP in 1944. He was also a member of Community Baptist Church, and served on the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals and Planning and Zoning Commission. By 1975 the branch had 650 members, making it the largest in Connecticut. Over time those numbers fell, and the NAACP branch has become inactive.

In the early 1960s New Canaan had around 350 Black residents.

The ‘New Canaan Experiment’ of 1969 to 1977 entailed bringing student teachers from Virginia’s historically Black Norfolk State College to town to teach in the public schools. The idea was to promote understanding and produce teachers who could cross cultural lines, and this soon after the assassinations of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy. The student teachers lived with host families. Eighty student teachers participated during the program’s successful eight-year run.

In 1972, a minister at the Congregational Church, and local leaders including the First Selectman and public school officials, raised funds to establish the ‘A Better Chance’ (ABC) program, buying a house on Locust Avenue. The program’s goal is to provide transformative academic opportunities to talented young men from disadvantaged backgrounds – first focusing on young Black men, and expanding to include those from all racial and ethnic backgrounds. Starting with the 1974-1975 academic year, the ABC Program has graduated many dozens of scholars, all of whom have gone on to college.