By Scott Herr

Last week I returned from a family reunion in Oregon. I got to see my parents and noticed that both of them have aged significantly even since the last time I saw them in February for my dad’s 90th birthday celebration. My father has always been sociable, but I was getting frustrated this trip because he would stop and talk with just about everyone he met. I’m used to moving along through my day and keeping a schedule. Chop! chop! It was exasperating at times to have to wait as he stopped to engage the people around him. I assumed this is just part of the aging process…

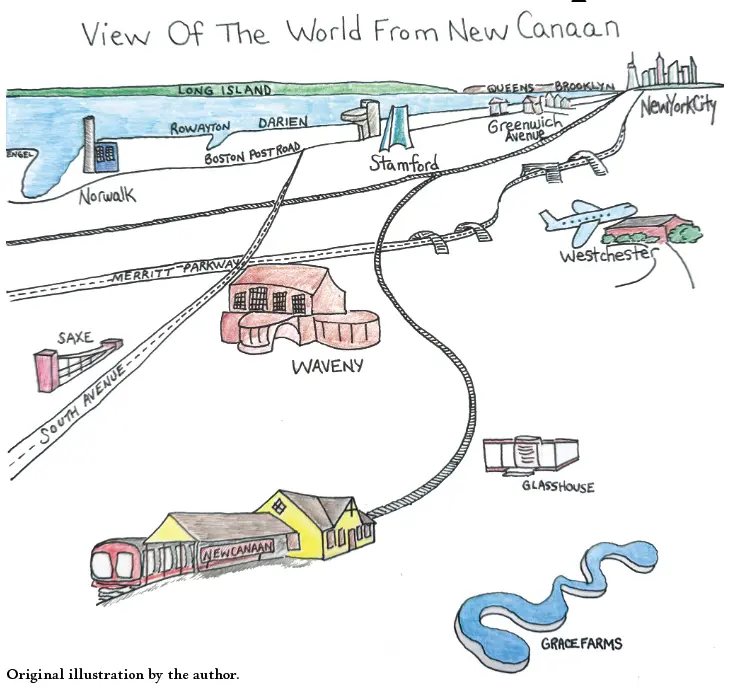

In a recent podcast, David Brooks, one of my favorite social critics and journalists, lists as one of his core values what he calls “epistemological modesty.” I love that phrase, which means Mr. Brooks leans toward humility about what he knows and what he can know. It reminds me of the adage that the opposite of faith is not doubt, but certainty! I would suggest “epistemological modesty” as a value worth employing as we move from summer and into a new season. It requires an open mind and a desire to be a learning leader (don’t we all think we’re leaders in New Canaan?), to approach each day with curiosity and an expectation that there is new knowledge and truth to be discovered.

Brook’s approach is particularly helpful advice for those of us with religious faith. In the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin there is an interesting quote from correspondence between Michael Welfare and Benjamin Franklin. Welfare was one of the leaders of the Dunkers, a German Anabaptist sect who were berated in the 1700s by vicious critics who were spreading lies about the Dunkers’ beliefs and practices. Benjamin Franklin suggested that Welfare publish the core doctrines and disciplines of the Dunkers for the public to understand better what they were really about. Welfare replied with these words:

“When we were first drawn together as a society, it had pleased [God] to enlighten our minds so far as to see that some doctrines, which we once esteemed truths, were errors, and that others, which we had esteemed errors, were real truths. From time to time God has been pleased to afford us farther light, and our principles have been improving, and our errors diminishing. Now we are not sure that we are arrived at the end of this progression, and at the perfection of spiritual or theological knowledge; and we fear that, if we should feel ourselves as if bound and confined by it, and perhaps be unwilling to receive further improvement, and our successors still more so, as conceiving what we their elders and founders had done, to be something sacred, never to be departed from.”

Franklin describes this sentiment as a “singular instance in the history of mankind of modesty in a sect.” Ha! Indeed, too many religious people are better described as arrogant religious zealots or fanatics. It’s sad that religious folks are not famous for our “epistemological modesty” or simple humility, but rather dogmatic stubbornness and moral arrogance. I confess I have often confused overconfidence with conviction, and argumentation with giving witness to my faith. I have been too slow to learn that true spirituality requires that we change our minds, and remain flexible to the new truths that God seeks for us to learn and that others can teach us as we move through life.

Jesus said, “I give you a new commandment, that you love one another. Just as I have loved you, you also should love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:34-35). Loving anyone, whether from your faith community, or your neighbor, or even your enemy (the high bar for Christian morality), requires “epistemological modesty.” Loving another person is not about evaluating the right or wrong of their politics, sex life, work ethic, marital (or legal) status, or level of education or income. Love requires seeking common ground (often times through asking questions) that allows you to recognize the humanity of the other, and to learn what it is they need in order to become more the person God created and calls them to be.

In her book, The Sovereignty of Good, British philosopher Iris Murdoch says too often we only look at people with egotistical and self-serving eyes. We look in order to figure out what we can extract from others, not how we can invest in them. Our goal, Murdoch argues, is to try and cast “a just and loving attention” on others. In fact, she says the act of looking at someone is itself the essential moral act. For Murdoch, paying attention is the central moral act, and I take that to mean by extension that asking questions and showing curiosity about what (or who) one is noticing is an equally important moral and life-giving act.

This may sound too simple, but a great way to start the new academic year is to notice and talk with the people around you. On the commuter train, strike up a conversation. In the grocery store as you move through the aisles, stop to talk with a neighbor. Engage people at your work or school over a coffee. Resist being consumed by your smart phone text messaging, email or latest game. Pay attention to the people around you, and show curiosity about what is going on in their lives. Ask simple questions, like, “How are you?” or “How is your day going?” and genuinely listen. Surprise: University of Chicago professor Nick Epley’s research shows people are happiest when they are talking to one another!

So, maybe my dad hasn’t simply lost his inhibitions, he’s discovered the simple wisdom for a happier life… and maybe we should too?