By Elizabeth Barhydt

In April 1975, as Saigon moved toward collapse, Chase Manhattan Bank sent a 27-year-old banker named Ralph White from Bangkok to Vietnam with a narrow assignment. He was to keep the Saigon branch operating as long as possible and, if closure became inevitable, evacuate the bank’s senior Vietnamese employees. He was chosen, as White later put it, “because I was 27 years old and was unmarried.”

What unfolded bore little resemblance to the plan.

White arrived in a city already unraveling. Enemy troops were closing in. Civil aviation into and out of Saigon had been terminated. The Vietnamese government prohibited its citizens from leaving the country. The U.S. ambassador refused to support evacuations of Vietnamese employees working for American companies, believing he could “negotiate” with the North Vietnamese to protect them after the fall. White thought the ambassador was “crazy,” particularly for instructing embassy staff not to evacuate South Vietnamese colleagues whose cooperation with Americans almost certainly meant imprisonment, torture, or death.

Within days, the distinction between authorized responsibility and moral responsibility collapsed. Senior Vietnamese staff urged White to evacuate everyone—clerks, assistants, drivers—and their families. That was far beyond his mandate. But White realized that once the city fell, no hierarchy would matter. The question was no longer whether to evacuate, but how.

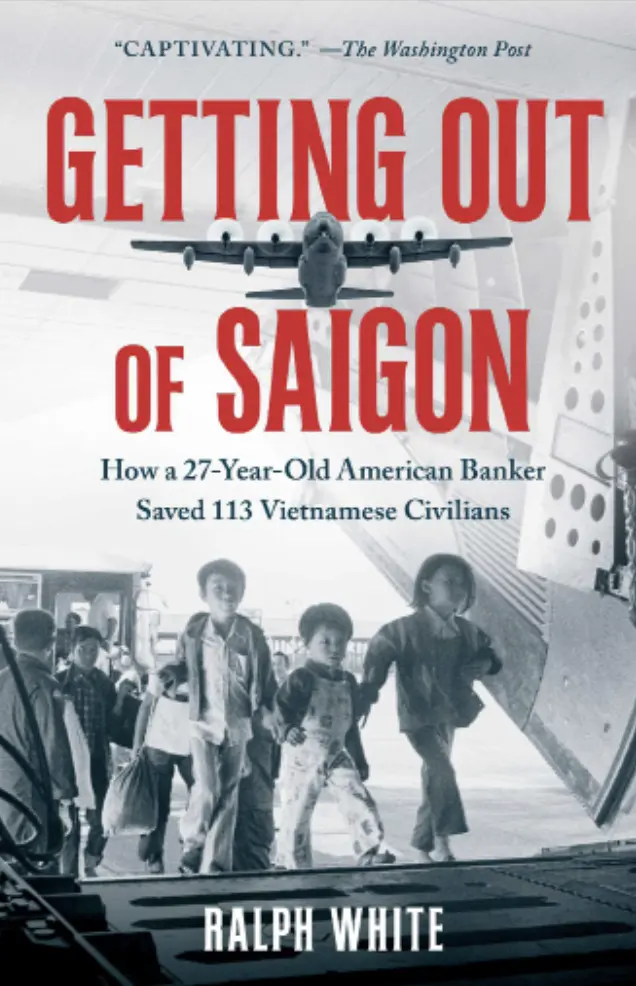

That moral pivot is the center of Getting Out of Saigon, White’s memoir published by Simon & Schuster in 2024. The book, described by The Washington Post as “captivating,” and by The Christian Science Monitor as a story of “courage, resolve, and determination,” recounts how White helped evacuate nearly the entire Vietnamese staff of Chase Manhattan Bank and their families—113 people in all—during the final days before the North Vietnamese Army entered Saigon.

White’s account is not about defying institutions for sport. It is about what happens when institutions fail to keep pace with reality. He discovered that a clandestine evacuation channel was operating behind the ambassador’s back. White resolved to use it.

The path out was fragmented and uncertain. Embassy personnel, acting in direct violation of their ambassador’s orders, confidentially told White that he could have 55 seats on a bus to the airport. He had roughly 120 people to evacuate. It was an agonizing arithmetic of lives. He decided to move whoever he could.

Getting through the airport presented another barrier. White needed “transit papers,” documents intended only for relatives of Americans. He found the embassy official responsible for issuing them and explained his situation. The official paused, then handed him a stack of papers. White filled them out one by one, listing each evacuee as a “relative.” The group boarded a cargo plane with no seats and flew out.

White was left with guilt and despair about those still behind. Then the call came again. Another bus was available, this time with 70 seats. The second journey proved even more dangerous. South Vietnamese forces had established their own roadblock in front of the U.S. checkpoint, stopping buses and shooting civilians attempting to flee.

When a South Vietnamese officer boarded the bus, White was carrying a small handgun, brought from his background as a hunter. “I’m not proud of it,” he later said, “but I came within a hairsbreadth of pulling my gun when that officer boarded the bus.” The officer turned around and left. The bus passed through. The remaining employees and their families escaped just hours before the city fell.

Oprah Daily called Getting Out of Saigon “edge-of-your-seat.” The phrase is accurate, but incomplete. The book’s deeper force lies in its examination of moral choice under compression. The Christian Science Monitor wrote that White’s story is about “the choice to do what’s right instead of what’s authorized.” That distinction animates every page.

The institutional reckoning came later. Anthony Terracciano, a former vice chairman of the Chase Manhattan Corporation, wrote, “In the history of the Chase Manhattan Bank, one event stands out as clarifying the bank’s responsibility to its employees. In 1975, Chase sent Ralph White to rescue its Vietnamese employees before the fall of Saigon.”

Years afterward, White was asked by his publisher to locate some of the evacuees. At a gathering organized by a Vietnamese expatriate group, an elderly woman sat beside him, listened, and said, “I know just the person to call.” That call led to reunions. White now receives invitations to weddings, births, and Lunar New Year celebrations from families whose lives intersected with his for a few decisive days.

White later returned to Chase’s New York headquarters, left as a vice president, earned an MBA at Columbia University, and founded the Columbia Fiction Foundry. But the defining chapter remains Saigon.

History often records institutional failure in abstract terms. White’s story records what happens when an individual refuses abstraction. Systems collapsed. Character did not.

White will recount these events for members of the New Canaan Men’s Club at its Friday, Jan. 9 meeting at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, 111 Oenoke Ridge. The meeting begins at 10 a.m., with White’s presentation scheduled for 10:40 a.m., following the business portion of the program.

The New Canaan Men’s Club is open to men age 55 and older and is currently accepting new members. Information about joining is available by email at ncmens@ncmens.info.