By Frank Gallo

Amherst Island, Ontario, February 1984. It was -5°f and nearing dusk. Trudging back through the deep snow with icicles hanging from my beard, I was the last to return to the warmth of my friends’ minivan. Rounding a corner, I noticed a Great Gray Owl perched on a post in a field about a hundred yards away!

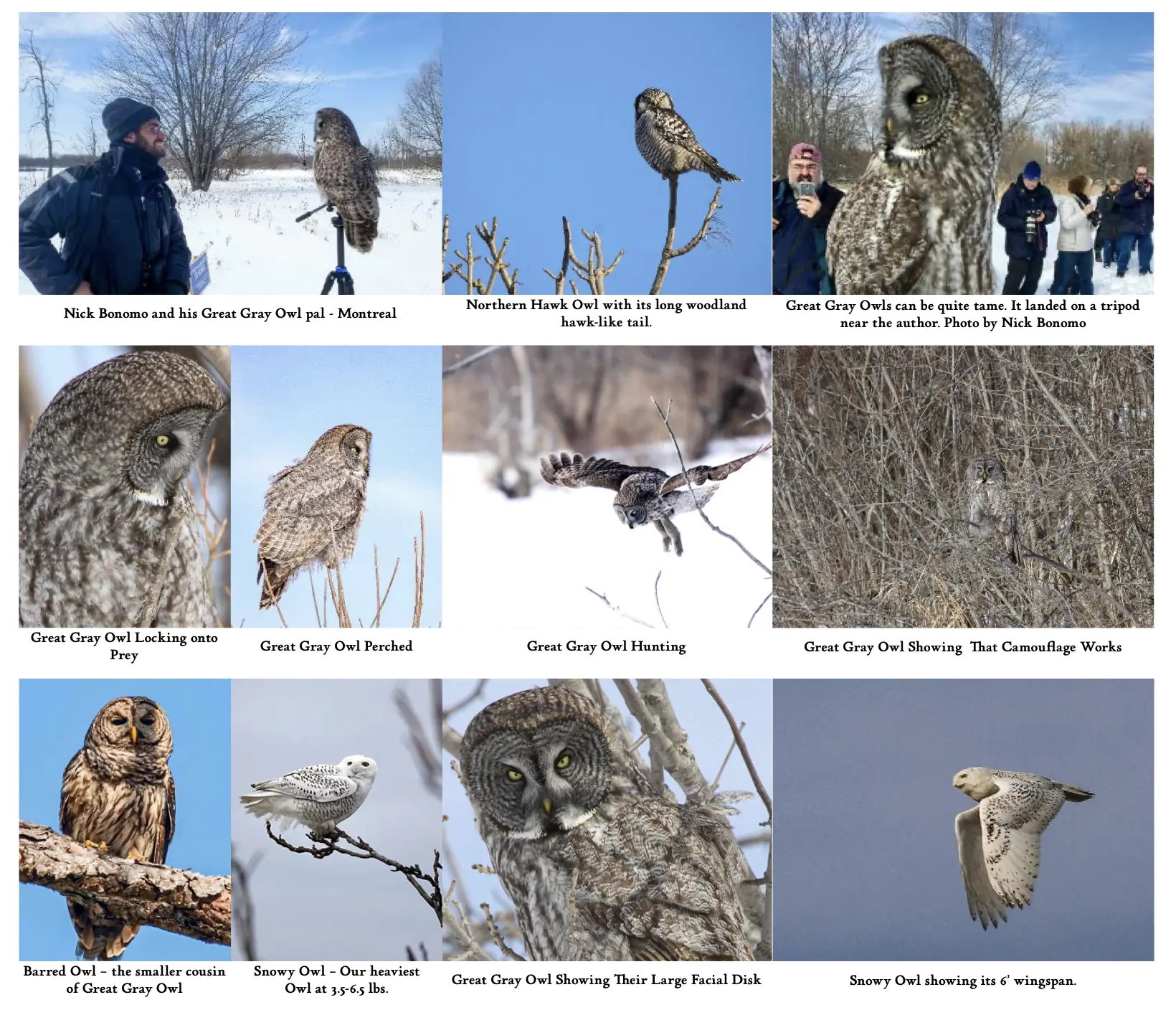

Great Grays are rare visitors to the northeast from the boreal forests of Canada and the western U.S. In most years few make it into the Northeastern U.S., so I’d come specifically to try and see one, along with Northern Hawk Owl, Boreal Owl, and Snowy Owl, the other Arctic and boreal breeders that seldom reach our area. Several of each were wintering in Ontario.

As I watched, the owl began bobbing its head up and down and side to side staring in my general direction. (I’m too big to be on the menu, but…) Suddenly, it seemed to lock onto something, launched itself from its perch, and flew towards me. When it was 20 yards away, it hovered over a three-foot snow drift, plunged feet first into it, and grabbed something. Slowly, it reached down with its bill and came up with a plump vole (a mouse-like rodent with a short tail) dangling from its beak. It glanced at me, then swallowed it whole.

Remarkably, the owl heard the vole from 80 yards away, was able to pinpoint exactly where it was under three feet of snow, and then caught it, all by hearing alone. I was awestruck. We stared at one another for a minute or two before it flew back to its perch, belly full, and I continued to the warm van a changed man.

Great Grays inhabit regions of the boreal forests of Canada and higher latitudes and elevations in the western U.S., which are consistently snow-covered. They and other owls have remarkable adaptations attuned to their environments and generally nocturnal habits. Their facial disk acts like a parabolic microphone to focus sound into asymmetrical ears – one is higher and differently shaped than the other – allowing them to triangulate prey by sound. Modified wing feathers with frilly fringes break up airflow over their wings making their flight nearly silent. They can maneuver deftly through trees at night using eyes packed with light-sensitive rod cells; eyes that are so large relative to their head size that in comparison humans would need roughly grapefruit-sized eyes to compete. Their eyes are tubular, which helps to enlarge an image on their retina, and encased in a hard sclerotic ring rendering them immobile. To compensate for the inability to move their eyes, they have 14 neck bones, twice the number in our necks. This allows them to turn their heads 270 degrees and look over their backs. Their eyesight is so sensitive that they can detect a mouse across a football field using starlight. Talons for catching prey and a sharp beak for tearing complete the package of these formidable predators.

I’ve always loved owls. One of my earliest memories is of a Barred Owl perched in a neighbor’s apple tree in New Canaan. When I was in my teens, local owl expert, Julio de la Torre took me under his wing and taught me to do what he coined “owl prowls,” where we would go out and call-in owls for others to see. When I first worked at New Canaan Nature Center from 1990 to 2005, he and I would lead public owl prowls at the Center. I practiced my Screech and Barred Owl calls for hours behind closed doors.

The tradition continues with our Owl Moon Night Hike scheduled for Saturday, January 31, from 7-8:30, where participants meet our captive owls used for education, then venture out with us to try to find owls on our grounds. I hope you can join us. Registration is required at https://newcanaannature.org/ night-hikes/.

When I was in college, my professor, the famous naturalist, Dr. Noble Proctor (Doc), took our ornithology class owling in the backwoods of North Branford at 3 a.m. We were walking along a secluded street towards a cemetery where Doc hoped to show us an Eastern Screech Owl, our smallest “tufted” owl. I was walking alone; two women were well up in front of me quietly talking, and Doc and the class a bit behind me. As we approached the cemetery, there came a blood curdling scream from within it that made the hair on my neck stand up. I froze. The two women shot past like a bullet, and I could hear the rest of the class stampeding away down the street. Doc quietly sauntered up and said, “What do think? Barred Owl?” I responded, “I was going to go with axe murderer, but sure, Barred Owl, let’s go with that.” We slowly approached the cemetery, and he turned on his flashlight. In his beam was a Barred Owl perched quietly on a branch as if he’d been waiting for us. Doc explained that male Barred Owls will sometimes scream during courtship. Owls. You bet! I was hooked.

At that time, I’d yet to see a Snowy Owl, the most likely, and perhaps the most beautiful, of the boreal and Arctic nesting owls to regularly reach our area, and I was determined to see one. So, I did some research and learned that although their cousin the Great Gray Owl is our tallest owl, with females reaching 33” in height, Snowy Owls are the heaviest, weighing in at 3.5 to 6.5 lbs., and have the longest wingspan, topping out at 6 ft. They nest on tundra in Arctic Canada and Alaska and across the Arctic worldwide and usually lay 4-5 eggs on the ground but can lay as many as 13 when food is abundant. Females and young of both sexes are white with black bars, and older adult males are nearly pure white. On the nesting grounds, males often perch near the nest on a high spot overlooking their territory. In years with a summer of bountiful food and successful breeding, Snowy Owls, especially young birds of the year, disperse south into the U.S. On occasion, they have made it as far south as Texas and Florida but are generally restricted to the more northern states. When the first reports of Snowy Owls in Connecticut started that year, I hightailed it to Stratford with a friend and we found one perched in a tree in Great Meadow Saltmarsh near Sikorski Airport!

In Connecticut, we can see Snowy Owls from late October to March/April, and rarely into May, often on coastal dunes and marshes and occasionally inland on open farmland. Not surprisingly, a large white owl is quite an attraction, and people will flock to sites where these owls occur. Unfortunately, this can lead to issues for the owl. As many owls visiting our area are young and inexperienced hunters, they are under a great deal of stress and often struggle to survive. Disturbance by enthusiastic viewers trying to get that selfie, or approaching too closely forcing them to fly, can cause them to starve. There have even been incidents where someone approaching an owl too closely f lushed it into oncoming traffic where it was hit and killed. So, please enjoy these wonderful birds from a respectable distance. (If they perk up, you’re too close). Certain owl species are no longer reported for fear of disturbance.

When the snow arrives, my thoughts often turn to owls, especially, the owls of the Arctic and boreal forests – Great Gray, Hawk, Boreal and, of course, Snowy, the species I hope to reconnect with each winter! Perhaps this will be another “owl year” when these beautiful Arctic predators venture south, and I’ll take yet another pilgrimage into the frozen north to see them!